by Ian Mann

July 10, 2019

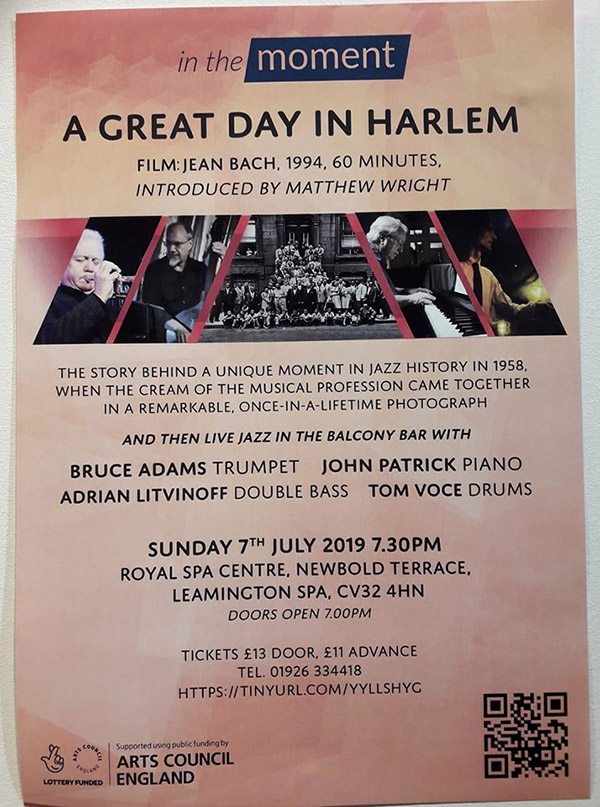

Ian Mann on a memorable night of film & live music with a screening of the celebrated jazz documentary "A Great Day in Harlem" followed by a live performance by trumpeter Bruce Adams and his quartet.

A GREAT DAY IN LEAMINGTON SPA

Film; A Great Day in Harlem (1994, directed by Jean Bach)

Live Music; Bruce Adams Quartet

Royal Spa Centre, Leamington Spa, 07/07/2019

Tonight’s jazz double film of film and live music was presented by local promoters In The Moment, founded by the former journalist and educator Matthew Wright and bassist, composer and all round mover and shaker Adrian Litvinoff.

The film/live music format is one that the pair organise once or maybe twice a year. Previous screenings have included the 1957 film “The Sound of Jazz” and the more recent Tubby Hayes biopic “A Man in a Hurry” (2015).

Tonight’s event took advantage of the facilities offered by Leamington’s arts and entertainments venue, the Spa Centre, with the film being shown in the Centre’s Studio / Cinema performance space before the audience made their way upstairs to the Balcony Bar to be entertained by live music from trumpeter Bruce Adams and his quartet.

A GREAT DAY IN HARLEM

Art Kane’s iconic 1958 photograph of a host (fifty seven to be precise) of New York’s most celebrated jazz musicians of the time photographed on the steps of a brownstone building in Harlem must be one of the best known and most widely reproduced images of any music genre. It’s one that I’ve seen replicated many times in music venues up and down the country, indeed there’s a framed print in one of my regular jazz haunts, the Queens Head pub in Monmouth.

I was aware of the existence of a film documenting the circumstances behind the famous photograph but I’d never actually seen it, and with all due respect to Bruce Adams, a musician whose playing I’ve enjoyed on a number of occasions, it was the prospect of seeing the movie for the first time that actually represented the main draw for me. The fact that Kane’s famous image was snapped in the year of my birth gave the film an additional resonance, along with the fact that virtually everybody pictured in, or involved with, the photograph is no longer with us. I suspect that the great saxophonists Benny Golson, born in 1929 and Sonny Rollins, born in 1930, may be the sole surviving musicians from that ‘Great Day’.

The screening was introduced by Matthew Wright, a sometime contributor to Jazz Journal, who informed us that it had been difficult for In The Moment to get hold of footage for the film, despite the fact that it was originally released as recently as 1994 and was critically acclaimed at the time. The original distributors of the film, Blue Dolphin, sold the rights to Universal, who subsequently passed them on to Sony. Wright unsuccessfully chased both Universal and Sony, who each seemed to have completely lost track of their investment. It was only when Bronwen Allsopp of the Spa Centre tracked down the film’s co-producer Matthew Seig that the footage became available, with Seig stating that occasions like tonight’s were exactly what the film’s makers would have wished for their work.

The enduring appeal of the film and of the music that inspired it was evidenced by an excellent turn out on one of the warmest days of the year and with plenty of rival attractions going on in the Leamington / Warwick area. The audience for the film was around one hundred, which I thought was very impressive given the circumstances.

The “Great Day in Harlem” film was the brainchild of director / producer Jean Bach (1918-2013), a print and broadcast journalist with a passion for jazz. She was aware of Kane’s photograph and was conscious that even thirty years after the shoot very few of the musicians involved were still alive. She undertook the task of interviewing many of the survivors on film, coming up with some sixty hours of material. For eighteen months she and editor Susan Peehl worked on the interview footage that Bach has captured, painstakingly paring down the material to create the hour long feature film that we were to enjoy this evening.

On the face of it “A Great Day in Harlem” is about one photograph, a single moment in time, but as the film makes clear there was far more to the occasion than that. Kane’s image has become definitive, but so many more photographs were taken that day, including cinema camera footage shot by Mona Hinton, the wife of bassist and composer Milt Hinton. Milt was one of the subjects of Kane’s photograph but asked Mona to film the events surrounding the photo shoot. Mona Hinton’s home movie footage is an integral part of Bach’s film and is interspersed with the more formal interview material assembled by Bach and Peehl. There is also archive material of some of the musicians playing live, this culled from previously mentioned “The Sound of Jazz” film which was originally filmed for CBS television and produced by Robert Herridge. The rights to that film are now owned by the Smithsonian Institution.

These components have been skilfully stitched together by Bach, Seig and Peehl to create a cohesive and illuminating overview of the occasion, which is given additional weight and gravitas by the voice-over of its prestigious narrator, Quincy Jones.

As we learned at the beginning of the film at the time his iconic image was snapped Art Kane wasn’t even a professional photographer. Instead he was an acclaimed art director working for a variety of American magazines. In the summer of 1958 Esquire magazine took the decision to publish a jazz edition. Its art director Robert Benton suggested that Kane, a jazz enthusiast, should be detailed to design the cover. It was Kane’s idea that the magazine should assemble as many jazz greats as possible for a communal photograph, scheduling the photo-shoot for 10.00 am on August 12th at 17 East 126th Street, between Fifth and Madison Avenue in Harlem.

Ten in the morning was an uncharacteristically early hour for the jazz musicians of the time, many of whom were used to playing in the clubs of 52nd street until three or four in the morning. “I never knew there were two ten o’clocks in one day” grumbled one early riser. Had it not been for the early start the roll call might have been even bigger, among those who arrived too late to be included in the definitive photograph were saxophonist Charlie Rouse, pianist/vocalist Mose Allison and drummer Ronny Free.

For Kane and his assistant Steve Frankfurt even establishing some kind of order among the musicians who had turned up on time represented something of a challenge. Many of the players hadn’t seen each other for a while and were more interested in chatting and joshing with one another than listening to the novice photographer. The local kids were fascinated by what was going on and at one point were playing around with Count Basie’s hat. Eventually Kane decided to feature the kids in the photograph, sitting them on the kerb in front of the musicians.

Kane’s attempts to organise the throng, which included using a rolled up copy of the New York Times as a makeshift megaphone, were documented by Mona Hinton’s movie camera. Bach, Seig and Peehel skilfully weave her footage into the film among the interviews and archive clips. There are also stills from Robert Benton, Milt Hinton and stride pianist Mike Lipskin who had attended the event as a protégé of Willie “The Lion” Smith. “The Lion” actually missed appearing in the definitive photograph having become bored with waiting around. He was taking a rest on the stoop of the building next door when the iconic image was finally captured.

Not that this prevented Smith from appearing in the film, which includes archive coverage of his playing, a series of stills taken on the “Great Day” and a discussion of the stride piano style pioneered by him and his great friend Luckey Roberts.

Of course “The Lion” wasn’t the only legend to be profiled during the course of a film that also included priceless live footage of such giants of the genre as pianists Thelonious Monk and Count Basie, cornettist/trumpeter Rex Stewart, saxophonists Coleman Hawkins and Lester Young, trumpeters Roy Eldridge, and Harry ‘Red’ Allen, bassists Oscar Pettiford and Charles Mingus and violinist Stuff Smith, all of whom had passed on long before the film’s release.

Even some of the musicians interviewed by Bach had died before the film’s eventual release, the project having been some six years in the making. These included trumpeters Dizzy Gillespie and Buck Clayton saxophonists Bud Freeman and Scoville Brown and drummer Art Blakey, all of whom appear as ‘talking heads’ as well as featuring in archive footage. Also featuring as an interviewee is the pioneering baritone sax specialist Gerry Mulligan who died in the year of the film’s release.

Other interviewees include saxophonists Johnny Griffin and Sonny Rollins, pianists Marian McPartland and Horace Silver and trumpeter Art Farmer, in addition to journalists and photographers such as Kane, Frankfurt, Benton and Lipskin plus Robert Altshuler and Nat Hentoff.

With such a wonderful set of contributors (and I haven’t mentioned all of them by any means) the film is chock full of anecdotes and observations that will delight any jazz fan. It’s interesting to note that the photograph features musicians from all the known genres of jazz at the time, from players rooted in the sound of New Orleans such as drummer Zutty Singleton to be-boppers and modernists such as Gillespie, Blakey and Mulligan plus such unique and indefinable talents as Monk and Mingus. The music’s roots in the blues are represented by the presence of powerhouse vocalist Jimmy Rushing.

Despite their stylistic differences all the musicians seem to get on well, as is evidenced both by the still photographs taken on the day and by Mona Hinton’s home movie footage. In a society less diverse than today the inclusiveness of jazz is illustrated by the presence of both black and white musicians and by the female musicians in Kane’s picture, pianists Marian McPartland and Mary Lou Williams and Maxine Sullivan. All three seem to have the complete respect of their colleagues.

McPartland is interviewed in the film and Sullivan and Williams are both profiled. Williams receives particular attention for her playing and arranging skills and was very much regarded as an equal by the male musicians of her time.

That said the photograph does reveal distinct factions, usually defined by choice of instrument. The drummers, in particular seem to stick together with Singleton, Blakey, George Wettling, Jo Jones, Gene Krupa and Sonny Greer all pictured together.

Once the iconic photograph was ‘in the bag’ Buck Clayton reveals that many of the musicians retired to Minton’s Playhouse, the venue widely considered to be the place of the birth of bebop, for further reminiscences, drinks, and no doubt, a jam session – which all seems very appropriate.

The edition of Esquire carrying the famous photograph was eventually published in May 1959 and the success of the venture led to Kane becoming a professional photographer of some distinction. He appears as an interviewee in Bach’s film, offering illuminating insights into the events surrounding the “Great Day”. Tragically he took his own life in February 1995, five months after the release of the film. Jean Bach, too is no longer with us, having passed away in 2013 aged ninety four. Meanwhile Mona Hinton (born 1919) died in 2008.

The “A Great Day in Harlem” title was first coined for the film by Bach, herself borrowing from the Duke Ellington song “A Sad Day in Harlem”. It has now been widely applied to the photograph that inspired it and in recent years a rash of “Great Day” photographs of large gatherings of musicians, from numerous genres and in various town and cities around the world have appeared. In the UK “Great Day” pictures have been taken in a number of different London locations and also in Birmingham and even in Leamington Spa. In May 2016 a gathering of Warwickshire musicians assembled in Leamington’s Jephson Gardens, among them bassist Adrian Litvinoff and drummer Tom Voce, who were appear with Bruce Adams later on for the town’s own “Great Day” celebration.

The Leamington “Great Day” picture was one of a number of artefacts relating to the film exhibited in the Balcony Bar, including a print of Kane’s photograph, together with a key identifying the musicians, plus various stills from the day in question. Matthew Wright displayed his personal copy of a book relating to the photograph that had been published in the US, which was a nice touch. He had also authored free audience handouts giving biographies of Jean Bach and Mona Hinton. Thanks, Matthew.

I had been loath to use the title “A Great Day In Leamington” for this feature, fearing that some might regard it as a little too facetious, but the existence of the photograph of the same name helped to change my mind.

I’d recommend any jazz lover to see this marvellous film. The Spa Centre crowd was totally captivated by it and a spontaneous round of applause burst out at the end of the screening. The archive footage is priceless, the anecdotes consistently interesting and amusing and the circumstances behind the creation of the photograph fascinating. Sixty years on Kane’s photograph represents a snapshot of another age, but Bach’s film acts as a reminder of the enduring power and appeal of the music.

For the record the roll call of musicians appearing on the photograph is;

Red Allen

Buster Bailey

Count Basie

Emmett Berry

Art Blakey

Lawrence Brown

Scoville Browne

Buck Clayton

Bill Crump

Vic Dickenson

Roy Eldridge

Art Farmer

Bud Freeman

Dizzy Gillespie

Tyree Glenn

Benny Golson

Sonny Greer

Johnny Griffin

Gigi Gryce

Coleman Hawkins

J.C. Heard

Jay C. Higginbotham

Milt Hinton

Chubby Jackson

Hilton Jefferson

Osie Johnson

Hank Jones

Jo Jones

Jimmy Jones

Taft Jordan

Max Kaminsky

Gene Krupa

Eddie Locke

Marian McPartland

Charles Mingus

Miff Mole

Thelonious Monk

Gerry Mulligan

Oscar Pettiford

Rudy Powell

Luckey Roberts

Sonny Rollins

Jimmy Rushing

Pee Wee Russell

Sahib Shihab

Horace Silver

Zutty Singleton

Stuff Smith

Rex Stewart

Maxine Sullivan

Joe Thomas

Wilbur Ware

Dickie Wells

George Wettling

Ernie Wilkins

Mary Lou Williams

Lester Young

BRUCE ADAMS QUARTET

Following a half hour break which allowed audience members to re-charge their glasses and look at the various “Great Day” exhibits we finally settled back to enjoy a set of live music in the Balcony Bar from the Scottish born trumpeter Bruce Adams and a local trio led by pianist John Patrick and featuring Adrian Litvinoff on double bass and Tom Voce at the drums.

Adams is a much respected figure on the mainstream jazz scene in the UK who has worked frequently with saxophonist Alan Barnes as well as leading his own groups. Well known for his dramatic high register playing he’s a musician that I first heard in the 1980s at the Ludlow Fringe Festival and more recently at the sadly now defunct Titley Jazz Festival in my home county of Herefordshire.

Adams is a hard working musician who gigs regularly up and down the country and who has become a hugely popular figure among British jazz audiences.

Tonight’s relaxed and good natured set was largely themed around music written by, or associated with, the musicians featured in Kane’s photograph. However in an initial deviation from that the quartet kicked off with “Rosetta”, written by pianist Earl Hines and a piece that acted as a vehicle for the soloing of Adams on trumpet, Patrick on electric piano and Litvinoff on double bass. This was a good introduction to the voices of the band with Adams demonstrating his power and fluency on trumpet while Patrick proved himself to be a wry and inventive piano soloist, concentrating on an electric piano or ‘Rhodes’ sound throughout. I was already aware of Litvinoff’s considerable abilities through his work with his own excellent Interplay quintet.

Adams switched to cornet to pay tribute to Rex Stewart on “Morning Glory”, a tune specifically written for Stewart by Duke Ellington. Apparently Adams’ cornet was once owned by the late Roy Castle and its new keeper used it to good effect on a blues tinged ballad that included some richly emotive playing from Adams. With Voce deploying brushes we also heard from Patrick at the piano before Adams moved back to the trumpet for the close.

“Robbins’ Nest”, written by saxophonist Illinois Jacquet, raised the energy levels once more with Patrick opening the solos, followed by Adams and Litvinoff and with Voce enjoying a series of fiery drum breaks.

The policy of alternating high energy numbers with ballads continued with Adams also featuring as a vocalist on a Roy Eldridge inspired version of Hoagy Carmichael’s song “Old Rockin’ Chair”. Ostensibly this may have been a ballad but we still got to enjoy some of Adams’ renowned high register trumpeting as he shared the instrumental solos with Patrick.

Two pieces from the pen of Horace Silver followed. First Adams switched to flugel for “Nica’s Dream”, written to honour Baroness Pannonica Rothschild, the “Jazz Baroness”, the British born heiress who did so much to support musicians like Silver and Thelonious Monk. Solos here came from Adams on flugel and Patrick on keyboard, their excursions underpinned by the buoyant Latin rhythms laid down by the impressive Voce, who also got to deliver a series of colourful drum breaks.

Silver’s “Strollin’”, which Adams dedicated to Flanagan and Allen, then featured Adams on Harmon muted trumpet, alongside Patrick at the piano.

A terrific version of Monk’s own Hackensack featured piercing high register trumpeting as Adams soloed in dynamic fashion above the crisp, driving rhythms of Voce and Litvinoff. Patrick followed at the keyboard prior to an extended bass feature for Litvinoff and finally a fiery series of exchanges between Adams and Voce.

“Some Time Ago” lowered the temperature once more with Adams moving back to flugel for a version of the tune inspired by the recording by flugel specialist Art Farmer and guitarist Jim Hall.

Solos here came from the leader on flugel and Patrick on gently trilling electric piano, or Rhodes if you will.

Finally a rousing send off in the form of Dizzy Gillespie’s “A Night In Tunisia” with Adams citing Gillespie as a major influence on his own playing. Introduced by Litvinoff at the bass Adams put a different slant on the piece by deploying a Harmon mute on his opening solo, his statement followed by final outings for Patrick on keyboard and Litvinoff on bass before Adams brought things to the boil with a second solo featuring the open horn.

Adams had delivered the show with a wry Scottish wit and although I suspect that the programme hadn’t deviated too far from his usual repertoire the fact that the material was loosely themed to complement the film was much appreciated. The leader’s own playing was excellent and the variety that resulted from the deployment of the three different horns helped to keep things interesting. The veteran Patrick impressed with his understated but richly imaginative solos while Litvinoff and Voce proved to be a supportive, flexible and versatile rhythm team who also made the most of the soloing opportunities that came their way.

Thus ended “A Great Day in Leamington”, the combination of film and live music working supremely well to create a highly memorable evening. The audience turn out must have delighted the organisers and helped to give the event an excellent atmosphere.

My thanks to Matthew Wright and Adrian Litvinoff for speaking with me afterwards and for putting on such an excellent night of jazz. Long may their work together as ‘In The Moment’ continue.

blog comments powered by Disqus