by Ian Mann

December 01, 2019

Guest contributor Trevor Bannister enjoys a performance of live music from the Stuart Henderson Quintet & a screening of the film ‘Blue Note: A Modern Jazz Story’ written & directed by Julian Benedikt

A Jazz and Film Tribute to Blue Note Records

Progress Theatre, Reading, Berkshire, Friday 22 November 2019

Stuart Henderson Quintet: Stuart Henderson trumpet & flugelhorn, Ollie Weston tenor saxophone; Tom Berge keyboards, Raph Mizraki bass, Simon Price drums

‘Blue Note: A Modern Jazz Story’ written & directed by Julian Benedikt

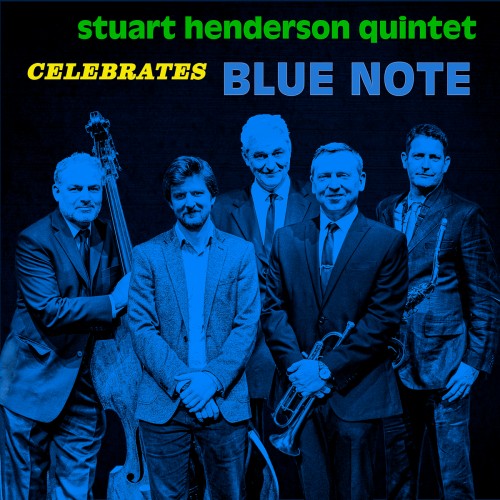

Like a classic Blue Note album cover, Zoe White’s accompanying image (see above) beautifully encapsulates the spirit and atmosphere of the Jazz at Progress double-headed tribute to mark the 80th anniversary of the Blue Note record label; an amalgam of the label’s distinctive sound as presented by Stuart Henderson’s Quintet and the visual images and voices of the label’s glorious roster of protagonists depicted in Julian Benendikt’s documentary.

Above all, the evening paid homage to the enduring genius of Alfred Lion, a Jewish émigré from Germany who founded the label in 1938 as a practical expression of his love for the blues. He presided over every Blue Note session until the label was sold to Liberty Records in 1966. Musician after musician recounted in the film that Lion could neither dance or keep time, but they marvelled at his innate sense of ‘Schwing’ and when a beaming smile lit up his face, they knew they had hit the groove. He just knew when things were right.

He was quick to pick up on innovative talent and to encourage original writing, providing both Thelonious Monk and Bud Powell with their first recording opportunities as leaders. When 22-year-old Herbie Hancock arrived in New York in 1963 to meet Lion at his office, armed with two blues and a standard as an offering for a prospective début album, Lion dispatched him to come up with some original material. The result - ‘Takin’ Off’ and a hit title in ‘Watermelon Man’.

By 1954 Alfred Lion had aligned a team of supreme talents to work the alchemy of producing jazz records: photographer and business partner Francis Wolf, the fastidious New Jersey based recording engineer Rudy Van Gelder, who had transformed his parents home into a recording studio, and the remarkable graphic designer Reid Miles, who designed the most outstanding of album covers but had absolutely no interest in the contents; he exchanged the records for classical albums. Blue Note had entered its classic period - cutting edge music that honestly expressed the identity of African-American society at that time. It was firmly rooted in the jazz heritage of blues and gospel, and at Alfred Lion’s insistence would always ‘schwing’, but so challenging that it veered towards the avant-garde.

Lion paid his musicians well. Trumpeter Freddie Hubbard used his first pay cheque to buy two new suits and a car. Perhaps, even more importantly, unlike most other record labels, he paid them to rehearse, so that the music was perfectly prepared in advance of the recording.

The same might be said of Stuart Henderson’s brilliant quintet which enthralled the near sell-out audience for the first half of the evening, presenting an astonishing 11 numbers drawn from the ‘golden era’ of Blue Note between 1954 and 1966. Make no mistake, this was no pale imitation of the ‘real’ thing, this WAS the ‘real’ thing. Music of the first order, played with impeccable musicianship and charged with an explosive force of emotional power and creative energy. There were times when, if you closed your eyes, you could have been listening to an original recording rather than a live band.

No tribute to Blue Note would be complete without Bobby Timmons’ ‘Moanin’’ and the faithful anthem, mainstay of a thousand jazz compilations opened the set, albeit as a short statement rather than the full-blown tune. Brief it may have been, but Simon Price’s Blakey-ish backbeat couldn’t fail to impress.

The band moved quickly on to ‘Blue Minor’ a number by the sadly short-lived pianist Sonny Clark. It bore all the qualities of great ‘hard bop’; an attention-grabbing theme, searing solos and hard driving ‘schwing’.

Horace Silver’s ‘Split Kick’, once a feature for Clifford Brown and Lou Donaldson on ‘The Live at Birdland’ album of 1954, set off at an even faster rate of knots and left one in no doubt about the expressive skills of Stuart Henderson on trumpet and Ollie Weston on tenor or the deft support of the rhythm section.

Horace Silver was a composer of tremendous versatility and his pioneering contribution to ‘Fusion’, the funky cocktail of jazz, blues and Latin rhythms is perhaps under-rated. ‘Cape Verdean Blues’ helped to set the record straight, and simply burst with the joyous vigour of a carnival parade.

In complete contrast, the brooding combination of Raph Mizraki’s bass and Tom Berge’s keyboard painted an unbearably desolate landscape of loss and regret in their introduction to ‘Autumn Leaves’, from the Cannonball Adderley/Miles Davis 1958 collaboration ‘Something Else’. Stuart Henderson sustained the mood to brilliant effect with his closely miked muted solo, while Berge’s coda, echoed by a final cymbal toll by Simon Price, was full of the pathos of what ‘might have been’.

The introverted tenor style of Hank Mobley was a great favourite of Alfred Lion, another case of him sensing something special about a player that escaped the attention of other listeners. Ollie Weston’s warm toned tenor paid a tribute to Mobley on ‘This I Dig for You’, a fine example of understated swing complemented by a tremendous and deservedly well received solo by Raph Mizraki.

In contrast to Mobley’s seemingly straightforward approach, Wayne Shorter expressed his ideas in a much more angular and abstract manner. Someone was heard to mutter ‘Good luck’ before the band embarked on the tricky configuration of ‘Witch Hunt’. They needn’t have worried. They completed the opening theme in masterful fashion and opened up the number to a string of fabulous solos – Henderson’s incisive trumpet, Weston’s haunting tenor and the economic ‘make every note count’ Fender Rhodes effect of Tom Berge’s keyboard. And all this, firmly underpinned by Mizraki’s bass and the propulsive drums of Simon Price.

Like Horace Silver, Herbie Hancock could (and still does) operate across the full spectrum of styles from funk to the most extreme avant-garde without ever losing his identity or musical integrity. ‘Dolphin Dance’, from the 1965 album ‘Maiden Voyage’ is one of his most lyrical compositions. The band, with Henderson on flugelhorn, captured the reflective mood to perfection.

‘Moment’s Notice’, from ‘Blue Train’, John Coltrane’s only outing on Blue Note, is that unique thing; a tune of incredible complexity that remains firmly fixed in your mind as the soloists work through all its possible variations. The band, with Ollie Weston to the fore, rose to the challenge magnificently, generating nail-biting excitement in the process.

Alfred Lion’s role in launching the career of organist Jimmy Smith, and in the process setting up a completely new style of jazz expression, was amongst Alfred Lion’s greatest achievements. With Tom Berge switching his keyboard to Hammond Organ mode, he set the groove for one of Smith’s biggest Blue Note hits, ‘Minor Chant’, a soulful number originally recorded with tenorist Stanley Turrentine on ‘Back at the Chicken Shack’.

And so, to the final number of a fantastic set. What else but Lee Morgan’s ‘The Sidewinder’, Blue Note’s greatest hit, and the success of which inadvertently almost bankrupted the company (the dreaded problem of cash flow).

***

As the band cleared the stage and the audience retired for an interval drink, the question came to mind ‘How do you follow that?’ It’s true, nothing could quite match the excitement of the first set, but that shouldn’t diminish the excellence of Julian Benedikt’s 2015 documentary film, ‘Blue Note: A Modern Jazz Story’, screened by kind permission of EuroArts.

Presented as a sharply edited montage of archive film clips, with startling visual images of the Blue Note stars at work on the recording sessions captured in perfect detail by the lens of Francis Wolf’s camera, and personal interviews, riding over a soundtrack of Blue Note recordings. It offered fresh insight into the life of Alfred Lion, especially his formative years in inter-war Berlin, where his imagination was first inspired by the posters for Sam Wooding’s All-Black ‘Chocolate Kiddies’ review and later darkened by the growing menace of Nazism.

If at times, the clips were tantalisingly brief, there were wonderful compensations; a full length cut of Albert Ammons and Pete Johnson in a dazzling display of boogie-woogie piano, a reminder that long before he lent an ear to bebop, Lion’s passion for jazz and inspiration for making records grew from his affinity with the blues.

Freddie Hubbard’s astonishing breath control as he took flight he on ‘Water Melon Man’ on a live date with Herbie Hancock; Tommy Turrentine, Bob Cranshaw and Al Harewood – three stalwarts of the Blue Note label, laughing and joking about Alfred’s inability to dance and his practise of paying by cheque, leaving them with the problem with where to cash it; shots of the label’s pressing plant - witness to the care that went into the production and packaging of each individual record; Lorraine Gordon’s wistful memories of life as Alfred’s first wife as she promised the ‘best seat in the house’ to a prospective customer in the chaos of her office at New York’s ‘Village Vanguard’ jazz club (clearly filmed long before the advent of TicketSource and their like…). She didn’t elaborate on the reasons for the marriage break-up. She didn’t need to. It was clear from the repeated testimony of musicians, jazz writers and his widow alike, that in ‘Alfred’s life, the music always came first’. ‘He wasn’t interested in making hit records or money,’ they would say. ‘Only great jazz.’ In an ocean infested with sharks, Alfred Lion stood out as a true gentleman.

The glorious chapter in the story of jazz documented in ‘Blue Note: A Modern Jazz Story’, may now be fading into the recesses of history, but the music lives on. The indefatigable figures of Sonny Rollins, Wayne Shorter and Herbie Hancock remain active and as creative as ever and it’s possible to easily download those once elusive albums to a mobile phone at the touch of a button. No doubt you could store the entire Blue Note catalogue on one device? And for those with deeper pockets, there’s always the thrill of seeking an original album and to feast the senses on its sound, the touch of its cover, the visual splendour of the graphics and sleeve notes and the scent of finest vinyl. Blue Note heaven!

Meanwhile, let’s look forward to the Stuart Henderson Quintet cutting an album of Blue Note tracks and making a return visit to Progress for a full gig in the not too distant future. Club promoters and festival organisers please note: the Stuart Henderson Quintet is as tightly organised, exciting and profound as any band operating on the UK scene … BOOK THEM NOW!!!!

***

Thanks are due to EuroArts, the Progress Theatre for making it possible to stage this unique double-headed event and the House Team for the excellent quality of sound and lighting and for the provision and operation of the projection facilities. And of course, special thanks to the audience for such generous and enthusiastic support.

TREVOR BANNISTER

Trevor’s Star Rating for this event - 4.5 Stars