by Ian Mann

March 02, 2022

Ian Mann enjoys the autobiography of multi-reeds player Jim Philip, co-written with regular Jazzmann contributor Trevor Bannister.

BOOK REVIEW

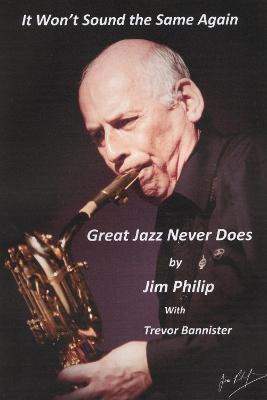

Jim Philip with Trevor Bannister

“It Won’t Sound The Same Again…Great Jazz Never Does”

(Springdale Publishing)

“It Won’t Sound The Same Again…” is the autobiography of the Scottish born multi-reed player Jim Philip (born 1941).

Philip is arguably not as well known to British jazz audiences as he might be, but this is partly due to the fact that the man is a polymath, he has been a talented sportsman, a successful businessman and an IT pioneer – in addition to being a highly accomplished jazz musician. Also he spent more than two decades away from the music scene as he pursued his business interests.

This recently published book will be of particular interest to Jazzmann readers as Philip’s co-writer is Trevor Bannister, the Reading based author who has been a regular contributor to the Jazzmann web pages since 2010. Trevor regularly covers jazz events at the town’s Progress Theatre and has also reviewed shows at other Berkshire locations plus the occasional gig in London. He has also covered a number of online events during the Covid pandemic, notably from the Boileroom venue in Guildford, and also authored a number of more general jazz related features, including a three part interview with Soft Machine drummer John Marshall. I am very grateful for his many contributions over the years.

With this book, issued via his own Springdale Publishing imprint, Trevor teams up with Jim Philip to tell the Scotsman’s remarkable life story. The seeds for the project were sown in July 2019 when Philip was part of the Remix Jazz Orchestra, who performed at Reading Minster as part of the town’s Fringe Festival. On that occasion Philip was playing baritone sax and bass clarinet but Trevor remembered having seen him play at Keele University many years earlier, during Philip’s tenure with pianist Michael Garrick’s Sextet. At that time Philip was playing tenor sax, flute, clarinet.

Trevor’s review of that 2019 Remix Jazz Orchestra show can be found here;

https://www.thejazzmann.com/reviews/review/the-remix-jazz-orchestra-the-evolution-of-the-big-band-reading-minster-read

Trevor subsequently saw Philip with the Remix Jazz Orchestra again at a Christmas concert at Finchampstead and as the two men continued to develop their friendship the idea for this book was mooted. Bannister had previously co-authored the late Michael Garrick’s book “Dusk Fire - Jazz in English Hands”, which was published in 2010, hence the strong connection between him and Philip.

The story in this latest book is told by Philip in the first person, so I’d guess that Trevor’s role was primarily that of an editor, although he does provide the book’s introduction.

Turning now to Philip’s life story, which is told via a prologue and fourteen full chapters. An only child James Alexander Philip was born in Aberdeen and the prologue gives brief summations of the life stories of his father Herbert (Bert) and Bert’s three brothers Alec, Richard and Sydney, collectively known as the “Four Brothers”, which, as Philip delights in telling us, is the also the title of a famous Jimmy Guiffre tune.

Having survived the war and the stock market crash of 1929 Bert set up a household stores / drapery shop in Aberdeen. The success of the business allowed him to pay for the young Jim to attend Robert Gordon’s College in Aberdeen where Philip excelled as an outstanding track and field athlete, the holder of many school records, and as a rugby player.

However his interest in competitive sport eventually became sidelined by a new found passion for music, and particularly jazz. It was 1956, Philip was fifteen and was introduced to the music by school mates Stuart Miller and Willie Gauld. Suitably enthused he expressed an interest in playing the clarinet and received a Boosey & Hawkes model for his birthday, his passion fuelled by the films “The Benny Goodman Story” and “The Glenn Miller Story”. Inspired by Goodman in particular he later formed his first trio with brothers Norman and Neil Simpson, who played piano and drums respectively.

Philip took formal clarinet lessons with Bill Spittle and joined the Aberdeen Schools Military Band. Inspired by his tutor Philip also acquired a tenor sax and began playing with other ensembles, notably the Jim Moir Band, at local dances.

On leaving school Philip became a trainee accountant whilst also playing in the pit band at Aberdeen’s Her Majesty’s Theatre, backing the singing stars of the time such as Andy Stuart Kenneth McKellar and Moira Anderson.

The young Philip continued to immerse himself in jazz, spending a large chunk of his wages on records and getting into Chris Barber, Alex Welsh and Sandy Brown as well as American artists such as Duke Ellington, Count Basie, Stan Kenton and particularly Maynard Ferguson. The Thad Jones-Mel Lewis Orchestra followed, as did Gerry Mulligan, Shorty Rogers, Art Pepper, Dizzy Gillespie, Cannonball Adderley, Quincy Jones, Gil Evans and Miles Davis – although Jim was later to draw the line when Miles ‘went electric’.

Philip agreed with his father that he would complete his accountancy qualifications before considering a full time musical career. At this time he continued to play with small groups, notably the Ian Stephen Sextet as well as with dance bands. Gordon Hardie opened a jazz club at Abergeldie Hall and the visits of artists such as Don Rendell, Graham Bond, Tubby Hayes and John Dankworth helped to steer Philip towards a more modern strain of jazz.

Philip joined pianist Munce Angus’ big band and also formed his own octet, the Big 8. This band featured original works by James Grant Kellas, who had returned to Scotland after studying in London, where he had played with Michael Garrick.

Meanwhile weekend sessions at the County Hotel in Perth found Philip rubbing shoulders with musicians who were subsequently to become famous, notably saxophonists Malcolm Duncan and Roger Ball (later of the Average White Band) and bassist Jim Mullen, who was subsequently to become better known as a guitarist.

On becoming a Chartered Accountant Philip looked for a way to combine work or study with playing music and applied to Brighton College of Technology to join a course titled ‘ Numerical Methods’, effectively a ‘Computer Science’ course. Philip was attracted by the regular rail services between Brighton and London, hoping to gain a foothold on the London jazz scene. His father felt that any qualification in this then new field of study would be a useful adjunct to his accountancy diploma. Philip made the long journey south in December 1964.

On arriving in Brighton Philip wasted no time in immersing himself on the London scene, travelling to ‘Town’ on the Brighton Belle and playing in the rehearsal bands of Graham Collier, Barry Forgie Pat Evans, Gordon Rose and ex Stan Kenton sideman Bill Russo. Many years later one of Collier’s rehearsal bands was to famously mutate into the now legendary Loose Tubes.

Philip’s hectic lifestyle, which combined academic study with music making and frequent travelling began to take its toll on his health and he decided to move to London, working in the computer / accounts departments of a variety of companies whilst pursuing his passion for music. Accessing the London jazz scene was now far easier and he established friendships with saxophonist / flautist Barbara Thompson, blues singer Bobby Breen and drummer John Marshall, among others. It was also at this time that Philip met his Swedish born wife Nina when he was playing a gig at the Gatehouse pub in Highgate.

The meeting with Marshall was particularly auspicious as the pair established a quintet featuring trumpeter Dave Holdsworth, pianist Mike McNaught and the prodigious sixteen year old bassist Chris Laurence. The group played at the Little Theatre Club, founded by free jazz drummer John Stevens, and at Ronnie Scott’s ‘Old Place’ in Gerrard Street.

When Ronnie’s moved to larger premises in Frith Street the ‘Old Place’ stayed open for a while, playing host to the rising stars of the day, among them pianist Mike Westbrook and saxophonists John Surman and Mike Osborne. The Jim Philip Five played there regularly and Marshall also played there with organist Bob Stuckey’s quartet, which featured South African saxophonist Dudu Pukwana. Famous American musicians such as saxophonist Ernie Watts would pop into the ‘Old Place’ for a blow after completing their engagements in Frith Street. Philip recalls that saxophonist Dave Liebman sat in with his quintet. These Trans-Atlantic alliances proved to be life changing for some British musicians, particularly bassist Dave Holland and guitarist John McLaughlin who both decamped to the states to work with Miles Davis.

The ‘Old Place’ also featured ‘Big Band Monday’, which featured the music of such composers and arrangers as Mike Westbrook, Mike Gibbs, John Warren, Graham Collier and Chris McGregor. Philip played with Collier and McGregor, the latter’s band a mix of South African and British players that eventually evolved into the Brotherhood of Breath. But it was Collier that first gave Philip his break as a big band soloist on a chart titled “Aberdeen Angus”, written with Philip and his tenor in mind.

Jim and Nina married in 1967, with John Marshall serving as Best Man.

Meanwhile Philip’s music career continued. He recalls a ‘cutting contest’ with fellow tenor man Stan Robinson in Cambridge, this followed two years later by the pair of them sharing a stage at the London Palladium as part of the band backing American singer Johnny Mathis.

Of more significance was Philip’s involvement with the New Jazz Orchestra, led by composer and arranger Neil Ardley. Barbara Thomson was already in the band and suggested Philip as the replacement for multi-reed player Don Rendell, who had left to concentrate on the quintet that he co-led with trumpeter Ian Carr. The reed section featured Thomson, Philip, Dave Gelly and Dick Heckstall-Smith, all of whom doubled on a variety of instruments. Carr remained with the band on trumpet & flugel and the line up also included trumpeters Derek Watkins and Henry Lowther, trombonists John Mumford, Derek Wadsworth and Mike Gibbs. George Smith was on tuba, Frank Ricotti on vibes, Michael Garrick at the piano and behind the drum kit was Jon Hiseman, Barbara Thompson’s future husband. Completing the line up was bassist Jack Bruce, later to find fame and fortune with the rock group Cream. Looking back now it reads like an A-Z of British jazz.

This line up recorded the album “Le Dejeuner Sur L’Herbe”, released in 1969. Although strongly influenced by Miles Davis, Gil Evans and John Coltrane the recording is now considered a classic of British jazz and Philip’s contributions on pieces such as Garrick’s “Dusk Fire” and Coltrane’s “Naima” earned him a nomination for “Talent Deserving of Wider Recognition” in that year’s Downbeat poll. The NJO toured the UK supporting pop and rock artists and recording broadcasts for the BBC.

One of these was released in 2008 as “Camden 70”, a BBC Jazz Club performance recorded at the Jeanetta Cochrane Theatre as part of Camden Jazz Festival. The ‘Dejeuner’ material appears alongside some later compositions. Many of the players remain the same, but notable additions include Harry Beckett (trumpet), Dave Greenslade (keyboards), Clem Clempson (guitar) and Tony Reeves (electric bass).

Philip ends this section by paying tribute to Thomson and Hiseman, the latter having left us too soon in 2018.

One time NJO pianist Michael Garrick invited Philip to join his sextet, a group that also included Henry Lowther (trumpet), Art Themen (reeds), Coleridge Goode (bass) and John Marshall (drums). This line up released the live album “Jazz Praises”, a jazz / choral work written by Garrick that was recorded at a concert in St. Paul’s Cathedral in 1968. Philip’s tenor was featured on the composition “Rustat’s Grave Song”, his horn replicating the sound of the Highland pipes. It was a performance of this piece at a Garrick Sextet gig at Keele University that first alerted Trevor Bannister to Philip’s talent.

Philip continued to work with the Garrick Sextet, with Garrick often playing the resident pipe organ at suitable venues such as the Central Hall, Westminster and the Royal Festival Hall, the first time the organ there had ever been played at a jazz concert. The band also played opposite vibraphonists Gary Burton and Red Norvo and the Ronnie Scott Nonet at George Wein’s ‘Jazz Expo ‘68’ at Hammersmith Odeon.

They also recorded several BBC broadcasts, including one from 1969 that was eventually issued as the LP / CD “Prelude to Heart Is A Lotus” by Gearbox Records in 2014. This features a different line up of the band with Ian Carr on trumpet, Don Rendell and Philip on reeds, Goode on bass and Trevor Tomkins at the drums. Philip primarily features on soprano sax, flute and clarinet with Rendell handling the majority of the tenor parts.

For the studio album “Heart Of The Lotus”, recorded in 1970, the Garrick, Carr, Philip, Themen, Goode, Tomkins line up was augmented by vocalist Norma Winstone, who was later to become a full member of the group, effectively replacing Philip.

Philip was beginning to find Garrick’s music too much of a technical challenge and instead elected to concentrate on the London Jazz Four, a group with which he was already involved. Nevertheless he and Garrick remained friends and Philip recounts that when he attended Garrick’s funeral in 2011 a piece from “Jazz Praises”, featuring Philip’s tenor, was played at the service.

In 1970 Philip achieved a lifetime ambition when he performed as part of Maynard Ferguson’s band at gigs in Swansea and London. This proved to be a frightening but thrilling experience and the book contains a couple of juicy Ferguson anecdotes.

Philip subsequently joined the jazz orchestra co-led by trombonists Bobby Lamb and Ray Premru, where he joined Duncan Lamont in the sax section. This line up recorded the album “Live At Ronnie Scott’s” for BBC Records in 1971. Later that year a second live set from the Queen Elizabeth Hall was released under the title “Conversations”. This performance was remarkable for featuring three drummers, the Orchestra’s own Kenny Clare plus star names Louie Bellson and Buddy Rich. This must have been a pretty incendiary performance, as was Philip’s later tenor ‘joust’ with a then ailing Tubby Hayes. Suffering from heart problems Hayes died shortly afterwards, aged just thirty eight. Philip mourns his passing.

In 1972 Philip left the Lamb – Premru Orchestra, again fearing that the technical challenges of the band’s music were beyond him.

The book’s next chapter looks at Philip’s time with the London Jazz Four. Philip’s own quintet, The Jim Philip Five was eventually forced apart by the demands made on the group’s members for participation in other projects, particularly Dave Holdsworth, Chris Laurence and John Marshall, the latter joining Ian Carr’s Nucleus and later Eberhard Weber’s Colours and Soft Machine.

Pianist Mike McNaught led his own London Jazz Four group, a line up with a piano/vibes/bass/drums configuration reminiscent of the Modern Jazz Quartet (MJQ). They had supported the Dave Brubeck Quartet, attracting the praise of Brubeck bassist Eugene Wright, and had recorded an album of Beatles tunes arranged in a jazz style by McNaught. “Take Another Look at The Beatles” had sold well, but the group’s vibes player, Ron Forbes was following a parallel career in the army and was posted to Germany.

Instead of replacing Forbes with another vibraphonist McNaught drafted in Philip on flute and Mike Travis at the drums, with Brian Moore remaining on bass. Following his success with the ‘Beatles’ album McNaught’s next project was “An Elizabethan Song Book”, a set of jazz arrangements of tunes from Tudor times that was released by major label CBS and actually did quite well.

Moore was replaced by Daryl Runswick and the quartet continued to play jazz arrangements of current pop tunes, building a substantial reputation at venues in London and the Home Counties, although hard core jazz audiences could sometimes be a bit ‘sniffy’.

The phrase “It Won’t Sound The Same Way Again, Great Jazz Never Does” first appeared as an advertising slogan for the London Jazz Four. The group played opposite Thelonious Monk and Rahsaan Roland Kirk at Ronnie Scott’s, but endured a salutary experience when playing to a nearly empty hall when supporting the Moody Blues. They added electric piano, sax and electric bass to their instrumental armoury and McNaught even experimented with an expanded line up featuring Henry Lowther (trumpet), Chris Taylor (alto flute), Frank Ricotti (marimba) plus a string section. One piece by the LJ4+ even found its way onto Youtube in 2012.

In the search for ‘crossover’ success the LJ4 changed their name to Atlantic Bridge and after a series of managerial misadventures, colourfully chronicled by Philip, they eventually recorded the album “Atlantic Bridge” for Dawn Records, Pye’s ‘progressive’ imprint. The recording was partly financed by the unexpected success of label mates Mungo Jerry and their enormous hit “In the Summertime”.

The album was made over the course of three days (a long time for what was notionally still a jazz act) and made effective use of the latest recording technology. The material featured two Beatles tunes, three Jimmy Webb tunes and one McNaught original. Reviews were mixed and the album, lavishly recorded and packaged, rather fell between two stools, too pop to be jazz, too jazz to be pop. It was also difficult to reproduce the sound of the album on the road, something which led to the eventual demise of the band, especially as McNaught, Runswick and Travis were also in demand for other projects. As the band’s business manager Philip felt that his commitment to the group wasn’t always matched by that of the other members and hence Atlantic Bridge came to the end of the road, but without ever officially disbanding.

At this juncture Philip packed his instruments away and returned to the ‘day job’. Even during a musical career that had seen him involved with some of the seminal albums of British jazz he had continued to work for Management Dynamics in West London and in 1972 Philip took up a post as Project Manager at Management Dynamics Software Services. He later worked for Data Logic and for ICL.

The next few chapters discuss Philip’s career in business and IT. As this is a music website and this review is nearly three thousand words long already and anybody reading it is likely to be a jazz buff I’m going to gloss over this aspect of the book. I appreciate that it’s been a vital part of Philip’s life, but as a music fan these tales from the boardroom hold little appeal for me. However technophiles may enjoy reading about how modern IT was developed, both in the UK and the US.

You may recall that the young Philip was a keen and accomplished sportsman, and although these interests were partly eclipsed by his greater enthusiasm for jazz he has always remained an avid sports fan.

One chapter of the book deals with his love for motor racing, and particularly Formula 1. Family holidays have been based around Grand Prix meetings and Philip once competed briefly in Formula Ford.

The motor racing chapter also includes a couple of nuggets for jazz fans. A visit to the US saw Philip checking out the Lighthouse Jazz Club at Hermosa Beach in California, which once hosted Shorty Rogers, Gerry Mulligan, Shelley Manne, Lee Morgan and others. He also toured the US headquarters of the Paris based Selmer Music Instrument company, visiting the day after Benny Goodman!

Philip has retained his love of rugby and is a fervent supporter of both the Scottish national side and the London Scottish Rugby Club. The chapter headed “Tales of the Funny Shaped Ball” features Philip’s reports of international and club matches involving his two favourite sides and his musings on the future of the game in the professional era. I’ll admit to a preference for soccer, but I’m also a follower of the ‘oval ball’ so I rather enjoyed this section.

The chapter headed “The Youth of Today” concerns Philip’s two daughters Jen and Tina and his grandchildren Luke and Phoebe and their own sporting and musical endeavours. Philip’s love for his family is obvious, but overall these are very personal reminiscences.

The final chapters of the book find Philip returning to active musical service. Philip’s retirement from the world of business and IT saw him unpacking his instruments after a lull of over two decades. Jim and Nina were now living in Gerrard’s Cross and Jim’s first engagement as he embarked on a second musical career was playing clarinet in the local wind band, very much a return to roots.

Although a little rusty Philip acquired a new alto sax, had his tenor restored and returned to jazz as a member of the BBO (Berks, Bucks and Oxon) Big Band, founded in 1986 by Roy Hole BEM. The BBO is renowned for playing charity events and has raised some £400,000 to date. He also played some gentle teatime jazz with small groups led by Pru Sharp and John Snow.

Philip returned briefly to the business world on the Isle of Wight before settling in Gerrard’s Cross. He took on a job with Dawkes Music shop in Maidenhead, the very place where he had had his tenor restored. Founded by saxophonist Jack Dawkes the shop specialised in reed instruments and customers included Art Themen, Karen Sharp and Simon Spillett. The company also had a dealership with Yamaha and Philip trained with the company and is now “the proud holder of a Yamaha brass and woodwind certificate”. The Dawkes business had strong links with local schools and Philip also enjoyed doing some teaching work for the company.

As Philip’s ‘chops’ began to return he sought more challenging musical situations than the BBO and the teatime bands. He joined the Chosen Few Big Band, led by the formidable Bill Castle, initially on tenor but later taking over the baritone chair when a vacancy came up. This occasioned the purchase of a Yanagisawa baritone sax at ‘trade’ courtesy of Dawkes music.

Although Philip was new to the baritone he quickly adjusted and also found work on the instrument with the Surrey Jazz Orchestra, led by Mike Wilcox, and the Blake’s Heaven Big Band run by ex-pat Australian Nick Blake and his vocalist wife Linda.

Philip had retained contact with his old friend Dave Holdsworth and the pair of them joined Brighton based trombonist Tim Wade’s nonet, an ensemble dedicated to recreating Miles Davis’ classic “Birth of The Cool” album.

In time the Chosen Few Big Band mutated into the Remix Jazz Orchestra as Bill Castle retired and bassist John Deemer took over the running of the band, with trumpeter Stuart Henderson appointed as MD. It was this line up that Trevor saw, and indeed helped to promote, at Reading Fringe Festival in 2019.

Now aged eighty one Philip continues to play with the BBO Big Band, Surrey Jazz Orchestra and the Remix Jazz Orchestra. The Covid pandemic engendered a period of reflection and the writing of this book. Assisted by John Snow Philip has also compiled two CDs of material sourced from old tapes and broadcasts, titled “A Younger Man’s Jazz” and “More from the Music of Jim Philip”. The latter also uses the “It Won’t Sound The Same Again…” slogan. These album features music by the Jim Philip Five, The London Jazz Four and the New Jazz Orchestra. These albums are not commercially available but are targeted towards family and friends. Similar arrangements exist for three Remix Jazz Orchestra CDs.

In 2017 the Atlantic Bridge album was reissued and remastered by Esoteric Records with the addition of two previously unheard bonus tracks. The reissue also included a comprehensive booklet and the release garnered a much more positive critical response second time round. Philip regrets the passing of Mike McNaught.

The final chapter tells the story of the two pianos that have been part of Philip’s life, the Challen upright from the family home in Aberdeen that belonged to his father and was later transported south to Jim’s home in Osterley Park, West London. It was the instrument on which Jim’s daughters learnt to play but was eventually replaced by a Klingmann grand piano, which remained with the family until 2006. Philip recalls one memorable occasion when the instrument was played by Liane Carroll, then pianist and vocalist with a band led by Dave Holdsworth. And it was the faithful Holdsworth who took on the instrument when the Philips downsized in 2006 after Nina suffered a heart attack, followed by a stroke. The Klingmann now lives in Holdsworth’s barn conversion in Devon. Philip sees the stories of these two instruments as representing “an allegory of life”.

The final section includes a comprehensive discography including Philip’s recordings with The London Jazz Four, Michael Garrick Sextet, New Jazz Orchestra, Atlantic Bridge and the Booby Lamb-Ray Premru Orchestra. The later compilations under his own name plus the Remix Jazz Orchestra are also listed. There are also extensive listings, including personnel, of numerous radio broadcasts.

Jim Philip has led a remarkable life. I was only really aware of him thanks to Trevor’s reviews of the Remix Jazz Orchestra but as this book reveals he rubbed shoulders with the very finest UK jazz musicians during the late 60s and early 70s, a time that can now be defined as a ‘Golden Era’ of British jazz. The New Jazz Orchestra albums and the Michael Garrick recordings with which he was involved can be considered truly ground breaking and his work with the London Jazz Four / Atlantic Bridge has now been re-evaluated and could be said to fall into the same category.

Philip has also achieved commendable success as a businessman and retains his passion for sport and music, and is still playing the latter in his early eighties.

As a jazz fan I found the music related chapters fascinating. Philip has worked with the best and the book features may interesting and entertaining anecdotes, far more than I can hint at here.

I couldn’t get into the business related chapters in quite the same way whilst the family reminiscences are essentially personal. I did find the motor racing and rugby sections interesting though.

This is one man’s life story, but as a book it’s uneven, as people’s life stories always are. There are so many aspects to Jim Philip that it’s difficult to maintain a coherent narrative throughout the book. But for jazz fans it’s an essential read for the music chapters alone.

Philip has enjoyed a musical career that he can look back on with pride – but who knows what else he might have gone on to achieve in this sphere had he had carried on in the 70s, which admittedly was a pretty bleak period for jazz, particularly economically.

“It Won’t Sound The Same Again…Great Jazz Never Does” is available from Trevor Bannister at;

Springdale Publishing, 34 Springdale, Earley, Reading, Berkshire, RG6 5PR. Price £15.00

Email; .(JavaScript must be enabled to view this email address)

blog comments powered by Disqus