by Ian Mann

February 25, 2013

/ LIVE

An absorbing evening of piano music that occupied the interstice between jazz and contemporary classical music thanks to the myriad possibilities offered by the combination of 4 hands and 176 keys.

Brad Mehldau and Kevin Hays, Town Hall, Birmingham, 21/02/2013.

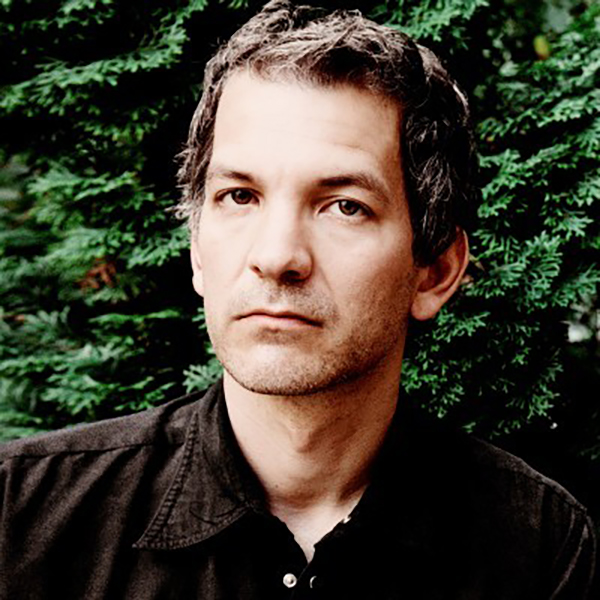

Pianist Brad Mehldau is best known for a series of recordings that have expanded the boundaries of the conventional jazz piano trio, particularly with regard to his artful deconstructions of songs by popular music composers ranging from Nick Drake through Paul Simon to Radiohead. In the company of bassist Larry Grenadier and drummer Jorge Rossy, the latter subsequently replaced by Jeff Ballard, Mehldau has continued to refine his approach, his playing exhibiting both a phenomenal technique and an intellectual rigour that has its roots in the pianist’s classical background.

As well as his celebrated trio recordings Mehldau has also released a number of solo piano albums and in 2011 collaborated with fellow jazz pianist Kevin Hays on “Modern Music”, a two piano set comprised mainly of tunes by the New York based composer Patrick Zimmerli. Zimmerli’s website http://www.patrickzimmerli.com describes his music as being “a sophisticated but approachable hybrid of jazz and classical music”, a definition that represents a neat summation of tonight’s performances of his material by the duo of Mehldau and Hays. Zimmerli’s compositions formed the backbone of the unbroken hour and a half (including encore) performance with his pieces punctuated by a series improvisations with the pianists taking it in turns to set the general musical agenda. Mehldau’s own website cites the pianist’s fascination with both the process of improvisation and the formal structure of music and emphasises the dichotomy of the presence of both the spontaneous improviser and the formalist within a single musical personality. It’s to the credit of both Mehldau and Hays that the improvisations here sounded as if they could have been written while the formal pieces often seemed to provide jumping off points for improvisation. It’s been the stated aim of many jazz musicians to blur the boundaries between composition and improvisation and this was something that the duo achieved here yet without ever losing their sense of discipline and focus.

The following quotes sourced from Hays’ website http://www.kevinhays.com offer a fascinating insight into the making of the “Modern Music” album;

“Patrick’s music is highly structured; the solos are generally a set length, but we opened it up a little”. (Hays)

“The improvisation was often not in our comfort zone?that is to say, usually, when a jazz musician improvises, he is working intuitively, allowing his intellect to be suspended for a while. This project was different, because Pat set up some unique challenges for us. One example among many: On Modern Music there’s a part that calls for us to improvise in the right hand while playing something written in the left hand. Sounds easy enough on paper, but it proved a real challenge for both of us.” (Mehldau)

Set up facing each other at two Grand pianos (both Steinways I believe) Mehldau kept the lid open whilst Hay’s remained resolutely closed allowing for a subtle variation of tone between the two instruments. Although this was a prestigious concert for the Jazzlines organisation the Town Hall was far from full with only the stalls being used, the circle and side boxes were completely empty. From my vantage point at the rear of the stalls the acoustics were excellent but with the two pianos situated side on to the audience and with no elevation of the seating it was difficult to follow the players’ hands on the keyboards. Thus some of the visual element of the performance was lost and for non musicians such as myself it was sometimes difficult to work out just who was doing what.

The last time I saw a jazz piano duo in concert was some thirty five years ago when I saw those two giants of contemporary jazz Herbie Hancock and Chick Corea perform at the Capital Jazz Festival in the grounds of London’s Alexandra Palace. I was a bit too young to appreciate the enormity of this event at the time but on a glorious summer’s day stretched on the grass banks of the Ally Pally grounds I seem to remember Hancock and Corea playfully sparring with each other, showing off their phenomenal chops and generally playing to the crowd. For all the technical accomplishments on show I recall it as being an essentially playful performance and I remember seeing Michael Garrick, who was seated a few rows in front of me, spontaneously applauding and whooping with delight at some of the inspired moments generated by two of his piano heroes.

If Hancock and Corea embraced the qualities of showmanship in a joyful and extrovert performance that celebrated their differences then Mehldau and Hays were more concerned with creating a sustained mood and and in presenting their pieces as the work of a single pianistic organism. For all the undoubted technique on show there was no grandstanding here and few real obvious “solos”. Indeed the atmosphere was closer to that of a classical recital than a jazz concert such was the air of discipline and intellectual rigour. Although the duo not chose not to play any of them tonight the “Modern Music” album includes Zimmerli’s arrangements of pieces by Steve Reich (“Music for 18 Musicians”), Philip Glass (“Excerpt from String Quartet No. 5”) and Ornette Coleman ( the supremely adaptable “Lonely Woman”).

It was Reich that came to mind as, thanks to the myriad possibilities offered by the combination of four hands and one hundred and seventy six keys, the duo constructed a mesmerising lattice of melody and counter melody this augmented by a similarly diverse range of interlocking rhythmic patterns and variations. Yet for all this the music remained eminently accessible and almost soothing at times.

Mehldau opened the evening as he led the duo into an exploration of Thelonious Monk’s “Think Of One” pausing at the end of the number to wipe his hands dry on a towel. This was music that obviously made huge mental and physical demands on the two musicians.

Although Mehldau is the better known of the two players and handled the bulk of the announcements this was very much a partnership of equals. Hays established the template for the first of the fully improvised pieces as Mehldau sat, eyes closed in Zen like concentration as he honed in on the subtleties of his colleague’s playing before eventually entering the fray himself. The piece was full of rhythmic subtleties and variations yet without losing the sense of underlying lyricism that Hays had established.

Zimmerli’s “Modern Music” possessed both an arresting hook and a Reichian complexity that called for a vigorous interaction between the two pianists with Mehldau broadly concentrating on left hand melody and Hays on complex right hand rhythmic patterns.

Mehldau set the tone for the following improvised duet, the subtle gospel flavourings obliquely hinting at the style Keith Jarrett, a pianist with whom Mehldau is regularly compared. Certainly both Mehldau and Jarrett feel the need to get into a certain mental zone in order to maximise their performances. The need for the musicians to psyche themselves up in this way no doubt explains the reasoning behind the uninterrupted performance, getting “in the zone” twice a night would be just too much to ask.

The rest of the set featured Zimmerli’s “Generatrix”, an unannounced piece started by Hays and presumably an improvisation (although Peter Bacon’s Jazz Breakfast site suggests that it may have been Mehldau’s “Unrequited” from the “Modern Music” album) finally Zimmerli’s “Crazy Quilt”, the opening track on the “Modern Music” album. It’s a perfect title, one that sums up neatly the closely interwoven sound of this remarkable duo in all its complexity, yet referencing the very human simplicity and lyricism also implicit in the music.

The duo’s music was well received by an attentive and appreciative audience and the pair returned to play an encore with Hays taking up the vocal mic for the first time to introduce his own tune “Blue Etude” (sometimes simply referred to as “Bluetude”), a piece sourced from his 2010 solo album “Variations”.

This had been an absorbing evening of piano music that occupied the interstice between jazz and contemporary classical music. Where Hancock and Corea had thrilled with their joie de vivre and showmanship Mehldau and Hays drew in their listeners in more intellectual fashion, constantly fascinating the listener with nuances of melody and rhythm, their playing disciplined but not forbidding. For all its rigour this was still music that could be readily appreciated and enjoyed although a wider dynamic range and greater balance of light and shade would have been welcomed by some listeners.

Prior to the concert my wife and I were privileged to be invited to attend a reception at which Jazzlines Music Fellowships were awarded to Percy Pursglove, Lluis Mather and Dan Nicholls, three musicians with strong Birmingham connections. Congratulations to Percy, Lluis and Dan, a separate new story offers a fuller insight into these awards and the workings of the Jazzlines scheme. Among the famous faces at the reception were Django Bates and Jason Yarde who had both been involved in the selection process. Both were later seen to be highly appreciative of the music of Messrs. Mehldau and Hays.

blog comments powered by Disqus