by Ian Mann

September 02, 2020

/ ALBUM

Even by Schneider’s lofty standards the twin discs of “Data Lords” represent a highly impressive and very important piece of work that deals with weighty and significant subjects.

Maria Schneider Orchestra

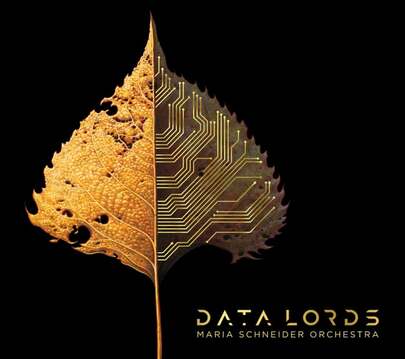

“Data Lords”

(ArtistShare)

Maria Schneider – composer, conductor

Steve Wilson – alto & soprano saxophones, clarinet, flute, alto flute

Dave Pietro – alto saxophone, clarinet, flute, alto flute, piccolo

Rich Perry – tenor saxophone

Donny McCaslin – tenor saxophone, flute

Scott Robinson – baritone saxophone, Bb, bass & contra-bass clarinets, muson

Tony Kadleck, Greg Gisbert, Nadje Noordhuis, Mike Rodriguez – trumpets and fluegelhorns

Keith O’ Quinn, Ryan Keberle, Marshall Gilkes – trombones

George Flynn – bass trombone

Gary Versace – accordion

Ben Monder – guitar

Frank Kimbrough – piano

Jay Anderson – bass

Johnathan Blake – drums, percussion

Released in July 2020 to great critical acclaim “Data Lords” is a two album set from composer and conductor Maria Schneider and her eighteen piece jazz orchestra. Subtitled “A story of two worlds” the work examines the relationship between humans and the digital and electronic technologies that shape modern society.

The two discs are subtitled “The Digital World” and “Our Natural World” and through her music Schneider explores the dichotomies and conflicts between the online world and the real world.

“No one can deny the great impact that the data-hungry digital world has had on our lives” explains Schneider. “As big data companies clamour for our attention I know that I’m not alone in trying to find space - to keep connected with my inner world, the natural world and the simpler things in life.

Just as I find myself ping ponging between a digital world and the real world the same dichotomy is showing up in my music. In order to truly represent my creative output from the last two years, it felt natural to make a two album release reflecting these two polar extremes”.

Born in rural Minnesota but long resident in New York Schneider’s writing has long been influenced by landscape and nature. Her 2015 album “The Thompson Fields” was inspired by the countryside of her childhood, while 2007’s “Sky Blue” had something of an ornithological theme. “Sky Blue” was my first introduction to Schneider’s intelligent and exquisitely orchestrated music and my review of that recording can be read here;

https://www.thejazzmann.com/reviews/review/sky-blue

In 2015 I was privileged to witness a performance of the “Thompson Fields” material by the Schneider Orchestra at Cadogan Hall as part of that year’s EFG London Jazz Festival. My account of that performance can be viewed as part of my Festival coverage here;

https://www.thejazzmann.com/features/article/efg-london-jazz-festival-2015-tuesday-17-11-2015

Since 2003 Schneider’s releases have all been made via the ArtistShare crowd-funding platform, which links artists with their audiences and ensures that they retain full control over their output.

If institutions such as ArtistShare represent one of the benefits of the connectivity of the internet Schneider is equally quick to condemn the big data companies- Google, Youtube etc. - for making it difficult for musicians to protect and keep control of their music, the supposition seeming to be that it should be given away for free. Her anger has led to her challenging the “Data Lords” by writing white papers and newspaper features, appearing on Copyright Office round tables, testifying before Congress and appearing on national TV.

“It makes me angrier than almost anything” she said in a recent interview for Jazzwise magazine. “The corporate greed of the big data companies. What troubles me most is that we are driven not by the music, not even by the technology, but driven by the corporate greed that knew data was the new oil. To gather the data they needed to get the eyeballs, to get the eyeballs they needed a carrot and music became the carrot. So they found ways to erode copyright, they found ways to make everything for free. They moved all around the very weak copyright laws and they built whole empires around the loopholes and then made the world expect music for free. Any thinking person who called out for copyright protection was labelled a Luddite, and they used words like ‘fair’ and free’ to make out that this was a liberal way of doing things – everything should be free where in reality it was the opposite of being ‘liberal’, the opposite of what they purport to be. The corporations are basically stealing work to become rich and incredibly powerful, and using surveillance to manipulate people”.

In another quote she has stated;

“Musicians have been the canary in the coal mine, we were the first to be used and traded for data”.

The elaborately packaged “Data Lords” contains an illustrated album brochure that name checks Schneider’s ArtistShare supporters and includes some superb black and white photographs of Schneider and her musicians, captured at the recording session by Briene Lermitte.

The brochure also includes Schneider’s detailed accounts, effectively essays, regarding the inspirations behind the individual compositions.

Disc one, “The Digital World” commences with “A World Lost”, in which Schneider recalls her own childhood in a world before mobile phones and other electronic devices, when moments of boredom would trigger some kind of creative activity, rather than an aimless trawl through social media. “Aren’t those moments our first blank canvas, blank slate, lump of clay or empty score page” she muses, before continuing “I think empty space makes us ripe for daydreaming and creativity”. She considers that today’s devices prevent young people from discovering their full creative potential, remarking “I mourn the loss of our internal landscapes just as I mourn the loss of our external landscapes”. The composition expresses a longing for “a simpler time when we were all more connected to the earth and to each other”.

Musically the piece reveals Schneider’s skills as a composer and arranger as she sculpts moods, colours and textures in a manner that has seen her routinely described as the natural successor to the great Gil Evans. “A World Lost” expresses her sense of mourning via the dark textures of melancholic bowed bass, mallet rumbles and the shadowy timbres of Ben Monder’s guitar, the fluidity and quiet intensity of his sound sometimes recalling that of Robert Fripp. The reeds and brass inhabit a world of grainy, low register textures, from which Rich Perry’s ruminative tenor emerges, blinking, into the half light.

The album features several commissioned pieces, among them “Don’t Be Evil”, the title of which satirises the motto of Google. “I’m not sure what’s most alarming, that they set the bar so low, or that they fail to reach even that most minimal aspiration” remarks Schneider, who goes on to provide a partial list of the corporation’s failings.

“This piece mocks Google as the cartoonish overlord that it is” states the composer, and this is reflected in a music with its tongue firmly in its cheek, but with the often grotesque humour also drawing attention to a real horror. There are shades here of Charles Mingus (particularly with Jay Anderson’s bass prominent in the opening stages), Frank Zappa and even Loose Tubes. Monder’s guitar again plays a prominent role, his solo here even more powerful and rock influenced than previously. Also making a big impression is Ryan Keberle with a rabble rousing trombone solo, while Frank Kimbrough’s piano solo combines sweetness with dissonance, a musical depiction of Google’s methods of suckering people in and exploiting them - without them even knowing that they’re being exploited.

“CQ CQ, Is Anybody There?” is a second piece to draw on Schneider’s childhood memories. Her father, an engineer by profession, was also a ham radio enthusiast, making contact with fellow ‘hams’ across the globe. In a sense ham radio could be said to represent the predecessor of the internet. But in contrast to the internet its practitioners had to follow a strict code of conduct, and also had to understand the technology, having to pass an exam before being allowed onto the airwaves. These were highly informed and very genuine enthusiasts. It was all very different to the commercially driven internet and the uninformed free for all of social media.

Ham radio relied on Morse code and Schneider’s piece is based around Morse code rhythms, these spelling out messages beginning with ‘CQ’ meaning “Is anybody there?”. Others include ‘power’, ‘greed’, ‘help’, SOS’, ‘AI’ ‘data’, and ‘this is WOABF’, this last her father’s call sign.

In Schneider’s ingenious score it’s not just the traditional ‘rhythm’ instruments that spell out the dots and dashes, it’s the brass and reeds too. Eventually soloist Donny McCaslin’s saxophone emerges out of the ferment of what the composer describes as “radio waves and Morse/ham chatter”, his tenor representing a human voice searching for expression and connectivity. What he finds is the radically treated trumpet sounds of fellow soloist Greg Gisbert, his electronically distorted sound being representative of dehumanised AI.

‘Sputnik’ also harks back to Schneider’s childhood, as she and her family followed the ‘space race’ between the USA and USSR on TV, culminating in the 1969 lunar landing. Today’s ‘space race’ is between the big data corporations, launching thousands of satellites into space, not all of them with benign intentions as the surveillance of the entire world’s population becomes a distinct possibility.

Schneider’s piece envisages a giant digital ‘exoskeleton’ circling the earth, comprised of the physical manifestations of metal and silicon and also the mosaic of data, a digital depiction of humanity.

The music evokes a suitably spacey ambience, the feel of the music gradually becoming more threatening and grandiose, with featured soloist Scott Robinson conjuring some remarkable sounds from his baritone sax.

“Data Lords” itself was the first piece to be commissioned and written for this project. It’s written from the perspective of a composer whose work, in monetary terms at least, has been devalued by the internet companies. But Schneider also fears the rise of Artificial Intelligence and its capacity to ultimately turn on its creators and destroy the human race, a doomsday scenario formulated by no less an authority than Stephen Hawking.

The music emerges out of a free-form intro that refers back to the Morse code messages of the earlier “CQ CQ”, gradually taking on a darker, sinister, threatening ambience, courtesy first of Monder’s guitar, and subsequently glowering brass and reeds. If Monder’s electric guitar sound is emblematic of the digital threat so too is the use of electronically treated trumpet, here played by soloist Mike Rodriguez. Meanwhile fellow soloist Dave Pietro’s baleful, but incisive, alto seems to symbolise the process of alienation as drummer Johnathan Blake clatters powerfully around him.

There’s a sense of the apocalyptic about the music here that is almost overwhelming, and the piece seems to end with the sound of the machines talking to themselves.

Disc Two, “The Natural World” is conceived as the antidote to its ‘Digital’ counterpart.

Schneider states;

“I can’t imagine I’m alone in often feeling desperate to get away from every device bombarding me with endless chatter, endless things, endless demands. Shutting it all down and encountering space and silence, I easily find myself drawn to nature, people, silence, books, poetry, art, the earth and sky”.

The pieces on this second disc take their inspiration from these things. Schneider has always harboured an interest in nature and conservation, as evidenced by her earlier “Sky Blue” recording.

The first of these pieces is “Sanzenin”, named after an ancient Buddhist temple and its gardens in Ohara, near Kyoto, in Japan. The music here is calmer and less cluttered, the textures softer and more muted. The featured soloist here is Gary Versace on accordion, an instrument rarely heard in jazz big bands or orchestras. In Schneider’s own words Versace’s role is to “take us on a joy filled stroll through the temple gardens”, a task that he performs beautifully, the high register trills of the accordion frequently resembling birdsong floating on the sumptuous textural undertow provided by the brass and reeds.

“Stone Song” is inspired by the work of potter Jack Troy, notably his wood-fired pieces. Following on neatly from the previous composition wood-firing is a Japanese technique in which no glaze is applied, the colours and designs coming from the interactions of minerals, chemicals and ash and forces such as movement and temperature.

“I think wood-firing has something in common with jazz” explains Schneider “Multiple spontaneous and mysterious forces beyond one’s own control will contribute to the beauty of the final work. Both require facing risk”.

Schneider’s composition is inspired by Troy’s work “ishi no sasayaki”, meaning “secret voice in the stone”. She approached the composition from the viewpoint of “a little stone, patiently waiting, maybe for months, years or even eons to be bumped, kicked, washed or pushed, to find oneself on a fresh side, catching a little light on its newly exposed colours or contours”.

The music itself is playful and whimsical, with Versace’s accordion again playing a role alongside Kimbrough’s piano, Blake’s percussion and the light and airy soprano sax of featured soloist Steve Wilson.

The title of “Look Up” links in with the previous “Digital World” disc.

“It’s something that the world needs to make a concerted effort to do again – whether looking at the sky, trees, birds, clouds or simply at each other” says Schneider. She doesn’t spell it out specifically , but it’s time for us all to look up from that mobile phone or other digital device.

Musically the piece was written as a feature for trombonist Marshall Gilkes, who shares the spotlight alongside pianist Frank Kimbrough. There’s a suitably relaxed and bucolic quality about the music with both soloists performing with great fluency and lyricism, supported by lush and rich ensemble textures. Gilkes, in particular, displays a remarkable facility on trombone, his playing warm and lucid, and transcending the limits of what is sometimes regarded as an ‘ungainly’ instrument.

“Braided Together” was inspired by the poetry of Ted Kooser, Schneider’s favourite poet and a fellow Mid Westerner, born in Iowa in 1939. The music is based on the text of Kooser’s poem “december 29”, a work from the poet’s book “Winter Morning Walks ; One Hundred Postcards to Jim Harrison”, originally published in 2000. Schneider also drew on Kooser’s work for the 2012 album “Winter Morning Walks”, her collaboration with the Australian classical soprano Dawn Upshaw.

Kooser’s words have the economy of a haiku, and this also applies to the music here with the versatile Dave Pietro adopting a very different tone on alto saxophone here, his sound pure, lyrical and conversational. Pietro is well supported by the rich ensemble textures and the responsive playing of a highly flexible rhythm section.

Schneider is a keen ornithologist, and her love of bird life informed her 2007 “Sky Blue” recording.

“Bluebird” is inspired by one of Schneider’s favourite birds, one which has also come to represent a symbol of hope. For once the composer’s introductory essay focusses on the good that the internet can do, citing the website of the Cornell Lab of Ornithology. This encourages the input of birdwatchers all over the world and encourages them to upload their own sightings, sound recordings, observations and photographs, adding to our understanding of birds and their place in the natural world. As Schneider comments “the internet doesn’t have to be all about secret surveillance, data exploitation, overreaching terms of use, and systems designed to make every human addicted to their services. It can be used to assist us all in making the world a better place.”

Musically the piece represents a typically multi-faceted Schneider composition that navigates many different moods and key changes, with important contributions coming from Kimbrough on piano and featured soloists Steve Wilson, this time on alto, and Gary Versace on accordion. The contrasting dynamics of the piece, and particularly Wilson’s powerful alto solo, demonstrate that nature can be ‘red in tooth and claw’ with Schneider’s text describing the territorial battles between blue birds and rival tree swallows.

The second disc concludes with “The Sun Waited For Me”, another piece inspired by a Ted Kooser poem, a second verse from “Winter Morning Walks” titled “march 20”. Schneider’s track title is taken from a line in the poem, but another line, “How Important It Must Be”, had previously been used for the closing piece in the Schneider / Upshaw song cycle. Schneider has since written the renamed instrumental version of the piece that appears here, a kind of orchestral chorale featuring the lead voices of Gilkes’ trombone and McCaslin’s tenor and with Versace also playing a significant role on accordion. If electric guitar and electronically treated trumpets embodied the spirit of the “Digital World” then Versace’s accordion represents their “Natural World” counterpart. Meanwhile McCaslin stretches our more expansively on tenor, reaching for the sun and the stars.

Even by Schneider’s lofty standards the twin discs of “Data Lords” represent a highly impressive and very important piece of work that deals with weighty and significant subjects. But leaving the polemic and politics aside it stands as a magnificent musical work in its own right.

Schneider’s reputation as the natural heir to Gil Evans remains unchallenged as she channels Gil’s spirit for the 21st century. On the first disc in particular I was also reminded of the work of Mike Gibbs, particularly due to the effective use made of Monder’s guitar. Gibbs has always had a fondness for working with guitarists, among them John Scofield, Bill Frisell and Philip Catherine.

The two discs are very different in terms of mood and texture, the first dark and threatening, the second lighter and more bucolic, with each having its own character but simultaneously forming part of a convincing whole. “Data Lords” has attracted almost unanimous critical acclaim and rightly so. It’s a work that is hugely impressive in its musical scope and represents a musical counterpart to Schneider’s political work and her harassing and lobbying of corporations and politicians on behalf of exploited musicians.

Schneider’s musicians are also worthy of great praise as they interpret her ideas with skill, grace and acumen. Many of the have played with the Orchestra for a long time and many featured at that EFG LJF performance in 2015.

Schneider, McCaslin and Monder famously worked on David Bowie’s final album “Blackstar”, with McCaslin leading the band and Schneider contributing the arrangement to the track “Sue (or In A Season of Crime”. She has cited the experience of working with the late Bowie as a profound influence, particularly upon the darker music to be found on “The Digital World” disc.

“Data Lords” is available exclusively from http://www.mariaschneider.com

blog comments powered by Disqus