by Tim Owen

April 20, 2011

/ ALBUM

"Ghosts" can be demanding, but it's no less invigorating for that.

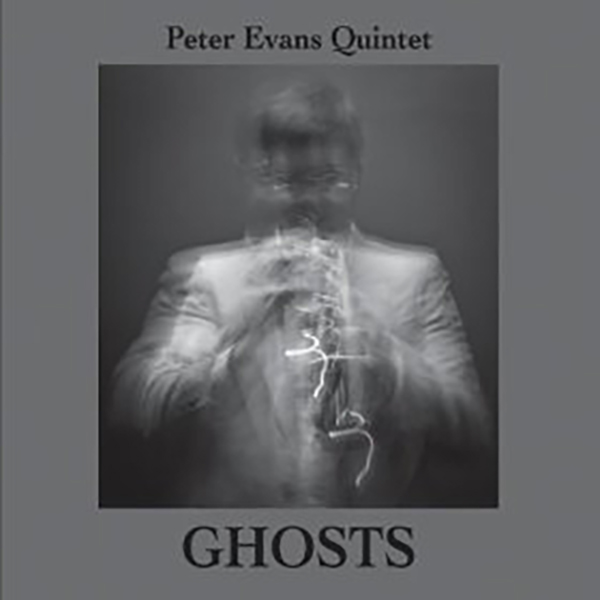

Peter Evans Quintet

“Ghosts”

(More is More)

Peter Evans’ 2009 “Nature/Culture” album included a document of one of the trumpeter’s solo live performances, in which processing was used to enhance his formidably honed ?natural’ techniques of embouchure and muting. The same period saw Evans take a front-line role in Evan Parker’s Electro-Acoustic Ensemble (as documented on “The Moment’s Energy”), amid a daunting roll call of sound processors and manipulators. It seems only logical, then, that Evans should now invite a laptop artist to participate in one of his own ensembles.

The bold impact of Evans’ last small group recording, the marvellous “Live In Lisbon”, was significantly due to the presence of Portuguese pianist Ricardo Gallo. Evans’ latest release, “Ghosts” (the first, incidentally, on Evans’ own More is More imprint), also features a pianist, but here it is the live processing of Sam Pluta that gives the music its particular character. Pianist Carlos Homs may be every bit as penetrating and forceful as Gallo, but his role here is more midfield, his contributions and those of his colleagues channelled into a collective syzygy. (It’s worth knowing, incidentally, that Homs has an ongoing project focusing on live electronic dance music, while Pluta is a leading light of the New York-based Wet Ink new music collective, and frequently works in a contemporary chamber music setting. Their disregard for the generally assumed schism between ?acoustic’ and ?electric’ was surely one reason why Evans was drawn to them.) At times, this Evans quintet operates in classic jazz mode, with Pluta’s laptop duking it out on equal terms with the acoustic instrumentation, but at others the core jazz quartet are in part (and perhaps, its hard to tell, sometimes in whole) refracted through Pluta’s laptop. The listener inevitably spends a good deal of time unpicking the group sound, attempting to fathom the processes at play: be that as it may, what we have here is rigorously composed free music with a bebop feel. The compositions are mostly by Evans, but Hoagy Carmichael’s “Starlight” is a graceful nod to tradition. Elsewhere, traces of Victor Young’s “I Don’t Stand a Ghost of a Chance with You” swirl spectrally in the background of “Ghost”, with Evans playing out his variations while with the piano trio improvise counter-melodies.

The album begins strongly with “?One to Ninety Two”, which is structured with the same conceptually daunting complexity as was Evans’ Lisbon material. There, Gallo rendered the contours of Evans’ structures with transparency and precision: the emphasis here is very much on Pluta’s processing, with Carlos Homs’ piano mostly restricted to the background. “Ghosts” is consequently more daunting and opaque, which is not necessarily a bad thing. On this track Pluta’s laptop often gives rise to sounds not unlike the slips, rips and backwards spooling of classic dub reggae productions, so drummer Jim Black is an astute choice to partner him. As exemplified by his own work with AlasNoAxis, Black is ever reluctant to play it rhythmically hard and straight where necessary, yet brings a questing intelligence to bear on every pulse, implicit or otherwise. As Black’s rhythm partner, Tom Blancarte is hardly less solid; in moments of heightened tension it sometimes sounds like he will thrash the strings right off the face of the bass, but his range extends to the contrastingly plangent.

As track “323” gets under way Jim Black gets into a percussive rumble with Pluta. Evans then imposes a repetitious theme statement, Homs pushes everything aloft on a surge of low-end piano, and Pluta rips out some pretty abrupt raspberries of electronic distortion. There’s a lot of nicely defined melodic shape in the moments that follow, but it’s another turbulent ride from start to finish. The subsequent back-to-back sequencing of “The Big Crunch” and “Chorales” is inspired. The former starts with Homs, Blancarte and Black trading blows before Pluta rips into them. It’s a dogfight, but a tuneful one; an aural vortex. The title, Evans notes tell us, invokes “the possible collapse of the universe on itself”“. In the fallout, we find ourselves in the mirror-world of “Chorales”, a weirdly nostalgic trip through some New Orleans-inflected be-bop, which gradually frays and degrades until only minimal repeating motifs of trumpet and piano remain. A concluding passage of close textural interplay evolves gradually from it, increasingly dominated by Blancarte’s bowed bass.

The opening of the quarter-hour of “Articulation” is assembled from discreet but compatible solos, and then played out as an ensemble piece once everything has come together. Evans’ pieces aren’t so complex that they seem simple; they sound pretty damn complex; but to listen to a talented ensemble like this work things through and knit them together is pure pleasure. In his liner notes, Evans tells us that this piece was inspired by the works of Woody Shaw, and in Evans handling of his material, as in his intonation, you can hear the legacy of Shaw’s marriage of dazzling technical virtuosity to innovation exemplified. Taking the piece out by “treat(ing) a single line of rhythm to an unfolding complex of orchestration”, the quintet sound almost classically modernist.

Lastly, there’s that short, strange trip through Hoagy Carmichael’s “Starlight”, Pluta sets Evans off against his own mirror image, with strong accompaniment from Homs’ piano. Evans’ notes suggest there are actually two pianos played here but I assume one of them is a ghost in Pluta’s machine. In the end the only thing to do is to accept the layer of mediation that live processing represents as a given, to stop trying to pull this music apart and to appreciate it on a purely musical level. In works like “The Moment’s Energy”, Evan Parker has come to addresses this issue by (and sure, I’m simplifying) spotlighting each front line musician in turn, giving them solo space before their designated sound processor(s) set to work. Evans opts instead to integrate Pluta into the quintet on equal footing, toe-to-toe, leaving the listener to unpick the many-layered processes at work, if they so choose. This may make “Ghosts” demanding, but it’s no less invigorating for that.

blog comments powered by Disqus