by Ian Mann

November 30, 2020

/ ALBUM

Regardless of its source material “Everything All The Time” is a thoroughly convincing acoustic jazz record, and the playing by Simpson & his hand picked team is both exemplary & inspired throughout.

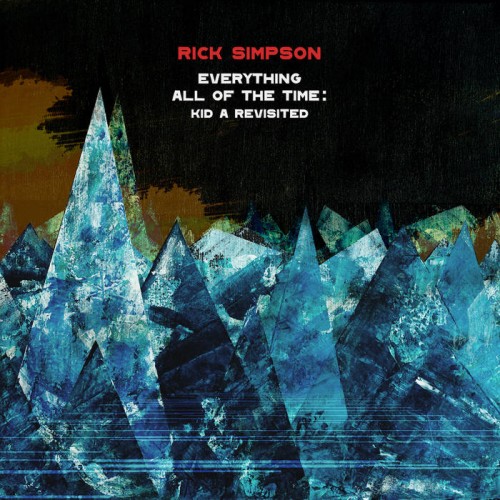

Rick Simpson

“Everything All Of The Time : Kid A Revisited”

(Whirlwind Recordings WR4765)

Rick Simpson – piano, Tori Freestone – tenor sax, violin. James Allsopp – baritone sax,

Dave Whitford – double bass, Will Glaser – drums

Pianist Rick Simpson has emerged as one of the stalwarts of the UK jazz scene and has appeared on the Jazzmann web pages on a number of occasions in his capacity as an able and versatile sideman. Among those with whom Simpson has worked are saxophonists Leo Richardson, Alice Leggett, Ruben Fox and Tommy Andrews, trumpeters Andre Canniere, Jay Phelps and Mark Kavuma and vocalist Sarah Ellen Hughes.

Simpson released his first album as a leader as long ago as 2012. The curiously titled “Semi Wogan” (Sayso Records) was a comparatively straightforward acoustic jazz performance featuring a quartet of Simpson, saxophonist George Crowley, bassist Dave Manington and drummer Jon Scott, with vocalist Brigitte Beraha guesting on one track.

2016’s “Klammer”, issued on the Two Rivers label, featured a set of nine original compositions by the leader performed by a sextet that also included saxophonists Mike Chillingworth and George Crowley, vibraphonist Ralph Wyld, bassist Tom Farmer and drummer Dave Hamblett. Simpson himself featured on both acoustic and electric keyboards, his choice of instrumentation suggesting an interest in music beyond the immediate jazz tradition.

This interest is further reflected in Simpson’s third solo project, an exploration of the music of the hugely influential rock band Radiohead, but within an acoustic jazz context.

Simpson’s liner notes best explain the inspirations behind the project;

“My musical interests began with electronic music, then jazz, and then Radiohead. All three were intense love affairs. The sonic landscape of Radiohead, in particular their electronic explorations, seemed to meld perfectly with my love of jazz and the avant garde. The Vortex Jazz Club generously offered a concert series where I could re-write popular albums as vehicles for instrumental improvisation. Naturally ‘Kid A’ was the first record I thought of.

2020 sees ‘Kid A’ turn twenty years old and its impact and inspiration on musicians and audiences alike is being felt to this day. I wanted to honour Radiohead’s original whilst re-writing the music to fit my vision as a composer, giving the musicians I chose for this project plenty of space to improvise and bring their unique musical voices to the forefront. For some tunes I wanted to stay close to the source material, for others they are merely referenced and serve as springboards for new composition or improvisation. I think we captured some of the fractured anxiety and beauty of the original”.

Simpson’s Vortex shows took place prior to lockdown and were a great success, reaching out to audiences beyond the usual jazz demographic. Suitably encouraged he took his chosen quintet into London’s Porcupine Studios and recorded this album over the course of a single afternoon session on 30th January 2020. “I think the time pressure contributed to the performances. It’s really punchy and to the point, but a lot happens – it captures the energy so well”, observes Simpson.

The album credits declare;

“All tracks composed by Radiohead

Arranged by Rick Simpson”.

The tracks are presented in exactly the same running order as the original “Kid A” album.

I’ll level with you here. Prior to hearing Simpson’s recording I have never previously consciously listened to the music of “Kid A”. That’s not to say that I don’t like Radiohead. I went through something of an ‘indie rock phase’ during the late ‘80s and a sizeable chunk of the ‘90s, mainly through working with a bunch of people who were younger than me, and getting into some of their music as a result. As workmates in a large organisation we inevitably ended up going our separate ways, and my rekindled interest in rock music declined as a result. I then found myself going back more and more to jazz, which I’d still been listening to alongside the indie stuff. Sadly the conversion process only seemed to work one way, I was singularly unsuccessful in trying to persuade any of the indie kids to listen to jazz!

All this is to say is that by 2000 I was listening almost exclusively to jazz and “Kid A” didn’t make it on to my personal musical radar. I’ve still got copies of “Pablo Honey”, “The Bends” and “OK Computer”, and still enjoy all of those. I even saw Radiohead live once, around the time of “Pablo Honey”, in the Wulfrun Hall, the smaller performance space at the Civic Halls complex in Wolverhampton. Frankly, at that stage of their career, they really weren’t very good and the diminutive Thom Yorke, with his bleached hair, came over as a pretentious little prat. I liked the feedback drenched racket the two guitarists cranked up though. But seriously, at that time nobody would have predicted just how big, or how influential, they would go on to become. My failure to engage with Radiohead in recent years is no reflection on the band, just symptomatic of my declining interest in rock and pop music in general, and a still growing obsession with jazz.

Forgive the personal reminiscences, but all this is by way of saying that this review of “Everything In Its Right Place” approaches the album as a jazz record in its own right first and foremost, and with no real prior knowledge of the source material.

Turning now to the music itself as the album opens with “Everything In Its Right Place”, effectively the title track. This sees the quintet quickly establishing their collective stamp on the music, with Simpson’s piano leading the way. He solos with great fluency and authority, while Farmer and Glaser negotiate the rhythmic complexities of the piece with skill and aplomb. Meanwhile Freestone and Allsopp combine effectively to supply additional colour and texture. The playing is, as Simpson observes, “punchy and to the point”. It also sounds totally natural and unforced, as if the piece had been specifically written for this particular acoustic jazz quintet.

“Kid A” itself commences with the sound of unaccompanied piano, Simpson’s gentle, halting explorations subsequently joined by reeds and rhythm as the music continues to develop. There’s a remarkably fluent baritone solo from Allsopp as the music continues to gather power and momentum, the two saxes then combining effectively as the music becomes more fractious, almost shading off into the realms of free jazz at times. “A finale of controlled chaos”, as Whirlwind’s press release puts it.

“The National Anthem” starts out in trio format, with Simpson’s Keith Tippett style piano surfing the fractured rhythms of Whitford and Glaser like a canoeist negotiating a set of rapids. We’re still in white water territory following the addition of the horns, as Simpson continues to slalom down a particularly tricky course, winding his way between the fractured rhythms of the bass and drums and the jagged edges of the horns. If anything the element of “controlled chaos” is even more conspicuous this time round in an intensely powerful performance. Simpson is particularly appreciative of Whitford’s contribution, remarking ““Dave earths the whole thing, with his beautiful, massive amazing sound.”

There’s a change of mood with the hauntingly beautiful arrangement of “How To Disappear Completely”, which features Freestone doubling on her second instrument of violin, helping to create the shimmering backdrop that frames her own melodic sax meditations. There’s an almost orchestral grandeur about the arrangement here, it’s almost impossible to conceive that this was an album recorded in the course of a single afternoon.

“Treefingers” maintains the contemplative mood and is introduced by Glaser at the kit, again cast in the role of colourist. His icy cymbal shimmers establish the mood of the piece and his dialogue with the leader’s piano is consistently engrossing.

As befits its title “Optimistic” raises the energy levels once more. Its propulsive, but captivatingly light footed and agile rhythms, help to inspire an engaging tenor solo from Freestone. This is followed by a darker, harder edged contribution from Allsopp as the music again gathers power and momentum, building once more towards the controlled chaos of the finale.

The deeply resonant sound of Whitford’s unaccompanied double bass introduces “In Limbo”. Piano and brushed drums are added as the piece develops in gently exploratory fashion, A ruminative solo from Simpson is followed by a probing tenor sax statement from Freestone. “She’s’ so free: she goes for it and doesn’t hold back, and she never plays any clichés”, enthuses Simpson.

Meanwhile the fiery, hard driving cross rhythms of “Idioteque” provide Allsopp with the opportunity to cut loose on baritone, displaying great power allied a remarkable fluency and mobility on the big horn. His playing also prompts a highly positive reaction from his leader;

“ his baritone playing is some of the most dark, vibey playing I’ve ever heard”, exclaims Simpson, before adding “Tori and James are such an amazing pairing”.

It’s rising star Glaser who takes the plaudits on “Morning Bell” with an evocative and skilfully constructed solo drum introduction. “Will is such a complete musician: he completely understands the right thing to do in any situation. He’s a little demon”, declares Simpson. The incisive interplay of the horns is followed by a brief passage of unaccompanied piano, this superseded by a more orthodox solo from Simpson with the group in piano trio mode. The effervescent Glaser continues to impress, his busy and inventive playing the perfect foil for Simpson’s outpouring of ideas. The multi-talented Glaser also painted the album’s front cover, a homage to the original “Kid A” artwork.

The album concludes with a contemplative, ballad style reading of “Motion Picture Soundtrack”, featuring Freestone’s brooding tenor sax incantations. She’s complemented by the sounds of the leader’s piano and the softly rolling thunder of Glaser’s drums. This is the sound of Radiohead as played in the ‘spiritual jazz’ style of John Coltrane.

I’m usually wary of ‘covers’ projects, but I have to admit that I was hugely impressed by “Everything All Of The Time”. Despite coming to this album with no prior knowledge of the music that inspired it I was impressed with the quality of Radiohead’s original writing, and also by Simpson’s arrangements. There is a rich variety of ideas here, particularly in terms of rhythm, colour and dynamics.

Regardless of its source material “Everything All The Time” is a thoroughly convincing acoustic jazz record, and the playing by Simpson and his hand picked team is both exemplary and inspired throughout, combining power and precision with a very spontaneous and infectious energy. The ‘live in the studio’ approach clearly worked superbly and credit is also due to Simpson in his capacity as producer, alongside the engineering team of Nick Taylor and Tyler McDiarmid.

Listening to this album is likely to move me to investigate “Kid A” for myself, but make no mistake “Everything All The Time” is a damn fine jazz record in its own right.

Nevertheless let’s hope that this time the process works both ways and that some of Radiohead’s international legion of fans will check out this rather fine interpretation of their heroes’ work by Mr Rick Simpson and his highly talented colleagues.

blog comments powered by Disqus