by Ian Mann

January 03, 2017

/ ALBUM

Carefully crafted, consistently beautiful music that has a way of getting under your skin and staying there.

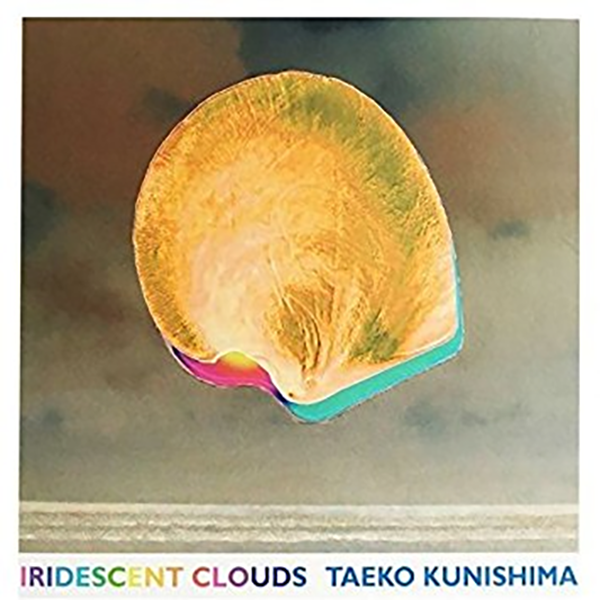

Taeko Kunishima

“Iridescent Clouds”

(33 Jazz – 33JAZZ258)

The pianist and composer Taeko Kunishima lived and worked in London for many years but in more recent times has been dividing her time between the UK and her native Japan, an arrangement necessitated by the need to care for her elderly mother.

Despite her hectic schedule Kunishima felt the need to “keep some space for musical creativity” and the album “Iridescent Clouds” is the product of this process. Recorded in the UK at two separate sessions in December 2015 and March 2016 the album is a convincing blend of jazz and world music styles, a kind of contemporary “third stream” music, if you will.

Naturally the music of Japan features strongly with Clive Bell playing the shakuhachi flute and Hibiki Ichikawa the three stringed Tsugaru shamisen. However Bell also plays the khene (or Thai mouth organ) and the Cretan pipes. Camilo Tirado’s tablas and other percussion add Indian and Latin flavours while Paul Moylan’s double bass underpins and anchors this undeniably exotic ensemble with further colour being provided by Jeremy Hawkins’ imaginative use of field recordings, including birdsong, human voices and the rustling of leaves.

Produced by Bell in conjunction with an engineering team headed by Nick Pugh the album, Kunishima’s fourth, features eight original compositions by the leader, the majority of them inspired by the beauties of the natural world.

Her approach is typified by the opening “Blue Clouds” which commences with the sound of running water and combines her lyrical piano with the exotic sounds of Tirado’s tabla and Bell’s wondrously atmospheric shakuhachi. Bell is one of the foremost European exponents of the instrument and also plays a variety of other ethnic flutes, pipes etc. He’s worked extensively with Jah Wobble and has been part of the bassist’s “Chinese Dub” and “Japanese Dub” projects. Others with whom Bell has collaborated include David Sylvian, Philip Clemo and former Can drummer Jaki Liebezeit. Bell is also a highly respected music journalist and writes regularly for Wire magazine.

There’s a gentle, episodic quality about the first piece but the following “In Search Of Time Lost” adds a greater urgency courtesy of Moylan’s robust bass lines and the rhythmic, banjo like twang of Ichikawa’s Tsugaru shamisen. Tirado’s percussion also helps to keep things moving and effective use is made of ‘found sounds’ including the sampled voices of a Japanese gathering. Bell’s shakuhachi is used more sparingly this time around but Kunishima’s piano is an almost constant presence as it weaves in and out of the piece in a manner that one commentator has likened to the wanderings of an individual lost within a large crowd and searching for a familiar face. Although different in feel to the opener the cinematic quality that distinguishes much of Kunishima’s output is again there in abundance.

Bell plays a greater role on the following “Iridescent Seashell” which opens with the sound of his shakuhachi twinned with Moylan’s bowed bass. Piano and percussion are added to the equation and the piece is similar in feel to that of the opener, similarly inspired by nature, as lyricism combines with musical exotica to create an almost zen like air of calm. Later in the piece piano and percussion are combined to charming effect with a field recording of the Uguisu Bird ( or Japanese Bush Warbler) – although one could just as easily believe that the sounds were generated by one of Bell’s flutes.

“Secrets” represents something of a musical interlude, a solo piano piece that features Kunishima in thoughtful mood, while again demonstrating her innate lyricism allied to a classically inspired lightness of touch.

Visual imagery plays an important role in Kunishima’s choice of tune titles. Moylan’s bass forms the foundation of “Lighthouse In Winter” while Bell’s wispy flute sounds like the searchlight beam desperately attempting to break through thick fog. Piano and percussion are deployed to atmospheric and dramatic effect and the piece ends with the sound of the sea, enigmatically unresolved.

As its title suggests “Oak Tree Leaf Rustles In My Mind” makes effective use of Hawkins’ field recordings. But perhaps the most interesting facet of this piece is the seamless blending of Japanese and Indian music traditions with Tirado deploying both tablas and gongs. Moylan’s grainy bowed bass approximates the sound of a tree creaking in the wind while Kunishima and Bell provide a balancing melodicism and lyricism.

Kunishima and Bell first played together in 2006 and the flautist subsequently appeared on two of Kunishima’s previous releases for 33 Jazz, “Red Dragonfly” (2006) and “Late Autumn” (2012), the latter also seeing Bell acting as producer. The chemistry that has developed between the pair is typified by the piano/shakuhachi (plus occasional percussion) passage that introduces “Everything Is In The Air”. Bell then switches to khene as the piece changes mood and direction, the harmonica like tones of the Thai instrument adding yet another intriguing flavour to Kunishima’s music as Bell’s playing is augmented by Tirado’s bright, lively, imaginative percussion. The piece then resolves itself with a gently lyrical coda featuring piano and bowed bass.

The album concludes with “Volcanic Rocks”, another piece with a strong cinematic quality. An evocative introduction features what I assume to be those Cretam pipes, their skirl augmented by the dramatic crashes and shimmers of Tirado’s gongs and cymbals. Tablas and bass then establish a strong groove, this punctuated by more atmospheric passages featuring bowed bass, the shimmering of percussion and the ethereal sounds of the shakuhachi with Kunishima’s piano the unifying force that holds it altogether.

Like the previous pieces “Volcanic Rocks” explores different sounds and different moods but still sounds unforced, organic and thoroughly natural. It’s the skill of Kunishima’s writing that draws these seemingly disparate cultural and musical elements together to create a thoroughly convincing whole and music with a strong cinematic and, indeed, spiritual quality. The playing is consistently excellent throughout and Bell’s production also serves the music well.

I’ll admit that when I first heard this album I was a little uncertain as to what to make of it. There’s little in the way of conventional jazz swing, which may deter some listeners, but this is carefully crafted, consistently beautiful music that has a way of getting under your skin and staying there, something that the intriguing and exotic instrumentation positively encourages.

I came fully prepared to dislike this record, yet find myself thoroughly recommending it.

blog comments powered by Disqus