by Tim Owen

February 12, 2009

/ ALBUM

At its best the unique marriage of big band and electronics works beautifully

Matthew Herbert isn’t really a Jazz artist. He’s best known as an innovator in the field of electronic dance music, specialising in micro house and working extensively with esoteric samples and field recordings under aliases such as Radio Boy and Wishmountain. Of his best known electronic works, Scale (2006) utilised hundreds of samples of everything from acoustic instruments to a coffin to breakfast cereal, while Bodily Functions (2001) used only samples of the human body. His Big Band is nevertheless the real deal, in the best tradition begun by ?King’ Oliver: a classic set-up of four trumpets, four trombones, four saxophones, piano, bass and drums, albeit with a twist.

As usual for a swing band, Herbert’s music is precisely arranged and presumably notated, and is played out live with improvised solos. The recordings, however, are subjected to electronic reconstruction by Herbert according to a set of self-imposed restraints (formalised as the rules of PCCOM). He has said that the results are more strictly orchestral jazz than traditional Big Band music. At its best, the marriage between big band and electronics works beautifully?kudos must go to Herbert’s arranger Pete Wraight?and is arguably more congruous than that, say, of Polar Bear and Leafcutter John.

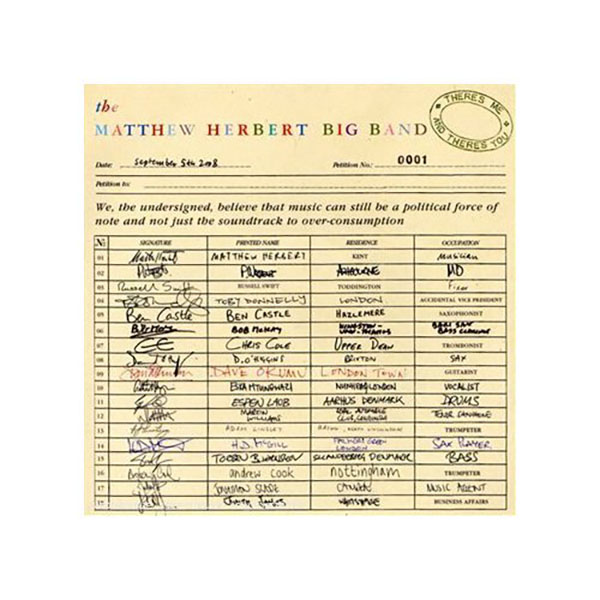

The band’s one previous recording, Goodbye Swingtime (2003), featured a number of guest vocalists, including Arto Lindsay and Jamie Lidell. Five years on, excepting a couple of changes in the horn section, a new rhythm team, and the recruitment of a single vocalist, the line-up for There’s Me is remarkably unchanged. Phil Parnell remains at the piano stool, and Dave O’Higgins still stands out among the saxophonists. Of the substitutions, Dave Green (bass) and Pete Cater (drums) have been replaced by Torben Bjoernskov and Espen Laub, a rhythm section that may be familiar to some readers as Parnell’s partners in his PP3 trio, as heard on Funky Feet (2006). The featured vocalist is Eska Mtungwazi, from Lewisham out of Zimbabwe. Her previous collaborations in the fields of rap, Jazz and nu-soul include those with Jazz men Soweto Kinch and Jason Yarde.

Mtungwazi is a forceful presence throughout, and it’s perhaps in reaction to her style that this incarnation of the band is more pugnacious than the former, though they are initially kept on a short leash. The first track, The Story, is more R&B electronica than what follows. Pontificate also emphasises vocals and electronic manipulations before introducing interpolations by the band. Waiting makes the first overt use of samples and field recordings, but also fully deploys the band. Next up, The Yesness is an infectious, punchy, up-tempo number, with charts for the full band and Mtungwazi suitably brusque and assertive.

This is a wonderfully balanced opening sequence, which incrementally draws upon the full potential of the band with restraint and keen attention to textural possibility and group dynamics. By contrast the semi-cryptic message of the next piece, Battery, dominates the music, while Regina is perhaps too didactic to be fully successful. The Rich Man’s Prayer is much more successful, taking things down-tempo and reinstating the focus on song form, with a full but subtle deployment of the band.

From here, the balance between music and message often tips too far off balance, as Herbert’s intentions and processes become more intrusive and the band are sidelined. Ambient samples introduce Breathe, with the band punching through at the mid point for a strong conclusion.

What follows is the album’s only real failure, at least for the casual listener. Knowing starts with cut-up voices, and then a mobile phone sounds, soon to be joined by others. There’s the sound of an audience responding with laughter. You have to read up on the track to know what’s going on here, and it’s a skit rather than a piece of music. Nonsound also makes much use of field recordings, but is more fully realised. Initial birdsong and tentative piano is enhanced by subdued horns and flute, until the music eventually breaks down into fragments of audio samples. The listener will probably not realise unless they refer to Herbert’s notes that the track uses samples “contributed by Palestinians of their favourite, or most hated sound”.

Similarly, I initially took the sample deployed for One Life to be sourced from a computer game: The many-layered truth is quite otherwise. Next up, Just Swing draws on the full richness of band for its titular up-tempo exhortation. It utilises a sample, among others, of a human cremation. Whether this cross-media form of intertextuality enhances or detracts from the listener’s experience will depend entirely on the limits of their curiosity. Don’t expect to be harangued though; the politics is mostly implicit in the detail. Here as on the vast majority of his endeavours, Herbert’s success stems from his willingness to entertain his listeners. Herbert is no ranter or holier-than-thou miserablist. The impact of There’s Me and There’s You is immediate, even somewhat overwhelming at first, and it’s a rich and totally absorbing experience.

As with Plat du Jour (2005), which addressed the politics of food production and marketing, Herbert’s intent is evidently not to browbeat his listeners but to engage and inspire them, and there is no question of the depth of his engagement. He would post a copy of his anti-corporate Radio Boy CD The Mechanics of Destruction (2001) free of charge to anyone who wrote requesting one. There’s much food for thought in each project that he undertakes, and likewise on the various accompanying websites. The site for There’s Me?matthewherbertbigband.com?is no exception. It offers a free MP3 download, provides details of PCCOM, and reveals the sources of the various samples used (e.g. audio from a neonatal unit, a landfill, and the House of Commons), as well as other curious facts.

blog comments powered by Disqus