by Ian Mann

May 19, 2015

/ ALBUM

A second strong showing on album as a leader from Crowley. Here is a young musician who is pushing his own musical boundaries and relishing the opportunity of doing so.

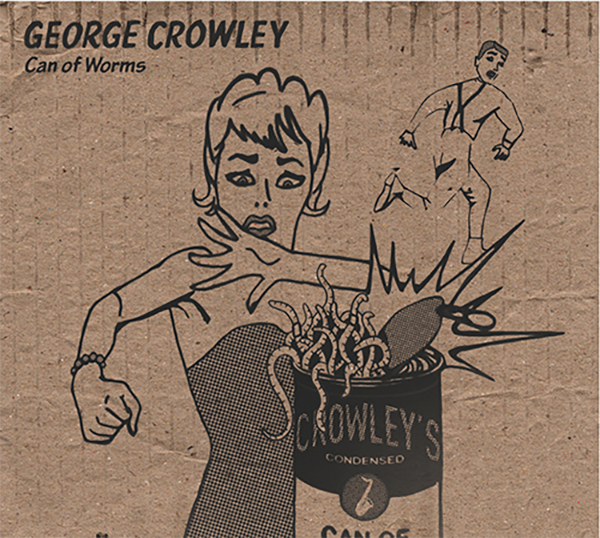

George Crowley

“Can of Worms”

(Whirlwind Recordings WR4666)

I first became aware of the playing of saxophonist and composer George Crowley in September 2010 when he gave an excellent performance at Dempsey’s in Cardiff in the company of pianist Kit Downes, bassist Calum Gourlay and drummer James Maddren. This same quartet subsequently appeared on Crowley’s outstanding début album “Paper Universe” (Whirlwind Recordings 2012), a record which amply confirmed his potential as both a player and a composer.

Since that time Crowley has been an increasingly influential and in demand presence on the London jazz scene as both a tenor saxophonist and as a bass clarinettist. His skills on the latter instrument have recently been highlighted at live performances by trumpeter Yazz Ahmed and saxophonist Julian Arguelles. Others with whom Crowley has worked include bassists Yuriy Galkin and Olie Brice, trumpeter Reuben Fowler and guitarist Moss Freed.

One of Crowley’s key musical alliances is with fellow saxophonist Tom Challenger with whom he performs in the latter’s collective Brass Mask. On “Can of Worms” the pair form a two tenor front line and the group also includes the versatile Dan Nicholls on piano and Wurlitzer - Nicholls also plays both reeds and keyboards for Brass Mask.

“Can of Worms” is now almost as much of a band name as an album title and the line up is completed by bassist Sam Lasserson and drummer Jon Scott. Virtually all the group members are part of the Loop Collective and the formation of the band came about as the result of the regular Loop Collective nights at The Oxford in Kentish Town where they found themselves thrown together as a pick-up band and quickly established a chemistry which Crowley decided should be explored further.

Originally from Norwich Crowley played in the same student band as Downes, trumpeter Freddie Gavita and vibraphonist Lewis Wright, all of whom are now professional musicians on the London jazz scene. He then completed a degree in English Literature at Cambridge before studying on the post graduate jazz course at the Royal Academy of Music where his saxophone tutors included Stan Sulzmann, Iain Ballamy and James Allsopp. He also acknowledges the influence of the great saxophonists of old, Lester Young, Sonny Rollins, John Coltrane, Joe Henderson, Warne Marsh, Wayne Shorter and Stan Getz.

“Can of Worms”, the album features seven original tunes by Crowley and represents something of a departure from the excellent “Paper Universe”. There appears to be a greater focus on improvisation and the presence of Challenger brings something of the energy and dynamism of a Brass Mask live performance to the session which was recorded at London’s Fish Factory Studio in July 2014. Crowley’s strongly melodic themes provide the jumping off point for vigorous group interaction and the balance between the written and the improvised and between the accessible and the abstract is excellent throughout.

Crowley has a fondness for literal titles and the album begins with his solo saxophone introduction to “The Opener”, this in turn leading to an invigorating group theme as the two tenors lock horns, sometimes doubling up to create the “fat” sound that Crowley craves. There’s a fiercely inventive solo from Nicholls at the piano followed by a more freely structured section featuring Crowley and Challenger in lively and highly interactive saxophonic conversation, a brightly sparkling dialogue that continues long after the theme comes back in.

“Whirl” begins with delicate keyboard sounds from Nicholls (the sound of his Wurlitzer presumably helping to give the tune its title) before progressing into an airily melodic theme which eventually acts as the launching pad for some more terrific two tenor interplay. It’s a tribute to Crowley that the piece seems to unfold perfectly naturally and organically, all the way from celestial keyboard tinklings to full on tenor exchanges.

“Ubiquitous Up Tune in 3” adds an air of breezy Latin lyricism to the proceedings with Crowley taking the first solo. Nicholls is again in inspired form at the piano, the album is a good advertisement for his abilities as a pianist following his recent absorption in more obviously electronic music.

Lasserson’s double bass introduces “Rum Paunch”, a kind of skewed blues that begins quietly with a delicately lilting sax melody, gently mellifluous piano and understated drumming. The quintet build the piece in unhurried fashion, gradually developing the theme as Crowley and Challenger snake around each other, playfully sparring as Nicholls’ keyboards insidiously needle and encourage. Eventually the sound approximates full on sonic brawling as the two saxes scream at each other, exchanging slurred insults to the accompaniment of Scott’s idiosyncratic drumming. It’s like a graphic musical depiction of the degeneration of a quiet night out down the pub into a drunken argument.

“I’m Not Here To Reinvent The Wheel” is one of the more conventional sounding tracks on the album with its fast paced, swirling Ornette-ish theme. The two reeds delight in exchanging phrases and solos above the busy, fast swinging rhythms generated by Lasserson and Scott. There’s a real air of joie de vivre about this piece as evidenced by the delighted laughter kept in at the end of the take.

“Terminal” initially finds the quintet in more contemplative mood with an atmospheric intro featuring, long moody tenor lines, shimmering Wurlitzer and Scott’s mallet rumbles. Lasserson’s bass riff ushers in phase two, the arresting theme and more relaxed mood prompting strong solo statements from both Challenger and Crowley these divided by the endlessly inventive Nicholls on electric piano.

“T-Leaf” closes the album, initially brooding gently as the two tenors take time to ruminate, to whisper rather than roar. It’s perhaps the most freely structured of all the pieces and includes a great drumming performance from Scott who conjures up an impressive array of sounds from his kit whilst always remaining receptive to what is going on around him. Eventually the pace begins to build and the five musicians coalesce at last to end the album on a unified note.

“Can of Worms” represents a second strong showing on album as a leader from Crowley. It’s less immediately accessible than “Paper Universe” but it is undoubtedly more adventurous and bodes well for the future. Crowley’s strong melodies are used to serve a robust improvisatory impulse and one senses that here is a young musician who is pushing his own musical boundaries and relishing the opportunity of doing so in the company of his friends. I’ve no doubt that the band Can of Worms had a whale of the time during the making of this album. Word has reached me that their live shows are hugely exciting too, I was disappointed at having to miss their gig at Dempsey’s in Cardiff earlier in the year but the word was that it was “terrific” and considerably better than the more conventional two tenor group led there just previously by Whirlwind label mate Alex Garnett.

Indeed one of the most impressive things about “Can of Worms” is how it avoids the clichés of the two tenor line up, no chases, no strings of competitive solos. Instead Crowley and Challenger are more about dialogue and interaction, although something of a competitive edge remains, playfully exaggerated on “Rum Paunch”. Crowley and Challenger also avoid any hints of Polar Bear type whimsy, an impressive feat for young contemporary players.

George Crowley’s next album as a leader will be awaited with considerable anticipation. It would be good to hear some of his bass clarinet playing on record too.